MILITARY HISTORY

On July 16, 1940 notes from an Interview Report stated that John Arthur Kingdon’s suitability for the Service was excellent based on his “good build; healthy mature appearance; intelligent; determined and deliberateness. His clothes were clean and neat”.

Pilot Officer John Arthur Kingdon – J 96325 – ACTIVE SERVICE (World War II)

July 16, 1940 John Arthur Kingdon completed the Attestation Paper for the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) at the RCAF No 11 Recruiting Centre in Toronto, Ontario. He was 23 years, 1 month old when, as a single man, he signed his Attestation Paper. John Arthur was born in Peterborough, Ontario and gave his birth-date as June 25, 1917, he did not have previous Military Reserve experience but had 4 years Public and High School Cadet Corps experience. His present address is 311 Brock St. Kingston, Ontario; permanent address is Box 386 Lakefield, Ontario. He attended the Queen Alexander Public School in Peterborough, Ontario from 1922 to 1926; the Lakefield Public School from 1926 to 1930; graduated Grade 8 and then completed 4 years of High School from 1930 to 1935 for his Junior Matriculation at Lakefield. From 1939 to 1940 John Arthur completed his and Senior Matriculation. John Arthur’s previous employer was his father, Orval (Orville) Edward Kingdon. He was employed in the Barrel Factory doing general work from 1935 to 1939; his Occupation was given as a Student. John Arthur was 5′ 9” tall, 36” chest, weighed 160 pounds, complexion medium and had blue eyes and brown hair. His next-of-kin was listed as his father; Orville Edward Kingdon of Box 386 Lakefield. Included in the references on his Attestation Paper were: W. A. Fraser, MP of Trenton, Ontario; Member of Parliament; J.F. Cox, Trenton, Manager of Trenton the Cooperage Mills and J.F. Harvey, Lakefield, High School Principal. On December 3, 1940 John Arthur’s medical was done in Kingston; it indicated that he was fit for duty with the RCAF. On December 18, 1940 John Arthur indicated that he was insured with the Manufacturer’s Life Insurance Company and the Prudential Life Assurance Company; his Insurance Premiums were being paid. Also on December 18, 1940 John Arthur Kingdon signed the Oath and Declaration in Ottawa, Ontario at the RCAF Recruiting Centre 90 O’Connor St. He was enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force as Aircrew for the duration of the War. He was then enrolled in the Rank of Aircraftman 2nd Class (AC2) [Private Recruit equivalent], with Service Number R 82313 and a Trade of Pilot – Observer, Standard Group.

On December 19, 1940 AC2 Kingdon was taken-on-strength with No 1 Manning Depot (MD) in Toronto, Ontario with the RCAF for basic training, while there he occupied public quarters. All training was part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (also known as the Joint Air Training Plan [JATP]). His basic training at No 1 MD, which generally lasted 4 to 5 weeks, would have included; ”how to bathe, shave, shine boots, polish buttons, maintain his uniform and otherwise behave in the required RCAF manner”. In addition there were; ”two hours of physical fitness education every day and instruction in marching, rifle drill, saluting, taking orders and getting use to other Military routines”. He also underwent an endless series of inoculations. On January 6, 1941 AC2 Kingdon was struck-off-strength from the No 1 MD and was taken-on-strength to No 1 Auxiliary Manning Depot (AMD), Trenton Ontario on January 7, 1941. The No 1 AMD conducted training which was designed to determine whether or not the student was capable of doing the Pilot Training regimen.

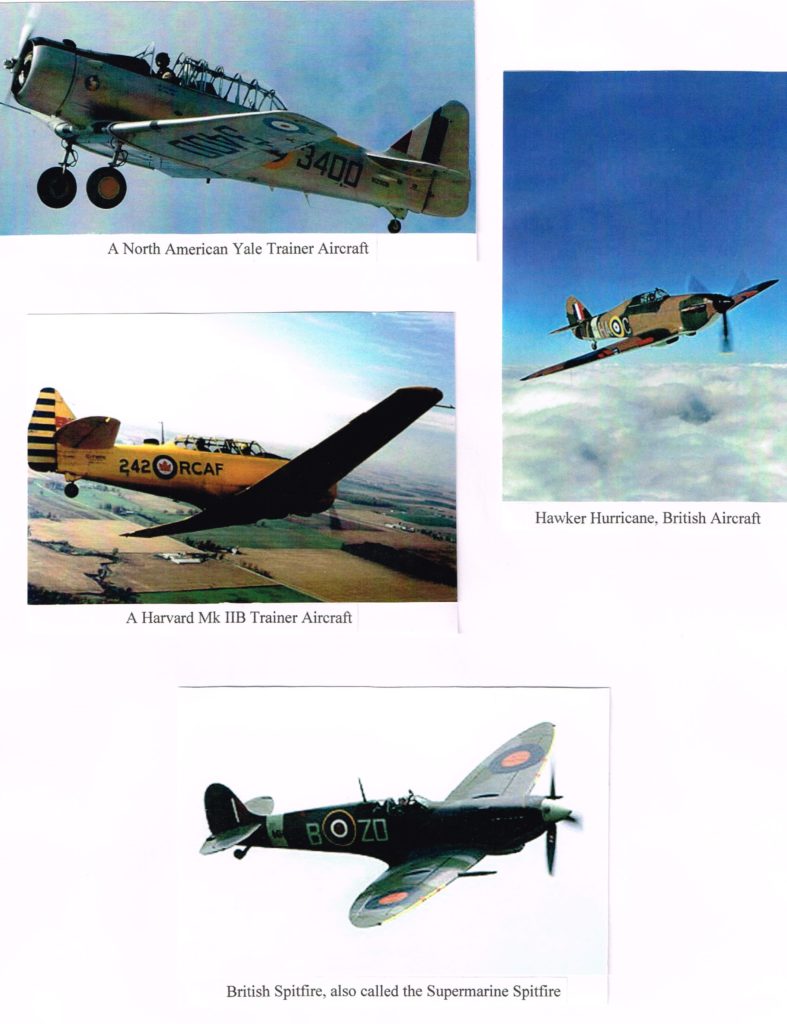

January 27, 1941 AC2 Kingdon was struck-off-strength from the No 1 AMD and was taken-on-strength as a supernumerary as a Security Guard at RCAF Station Trenton. April 10, 1941 he was struck-off-strength from RCAR Station Trenton and April 11, 1941 he was taken-on-strength to the No 1 Initial Training School (ITS) in Toronto. Pilot candidates began their training at an Initial Training School (ITS). They studied theoretical subjects and were subjected to a variety of tests. Theoretical studies involved ”navigation, theory of flight, meteorology, duties of an Officer, Air Force Administration, algebra and trigonometry”. Tests included ”an interview with a Psychiatrist, a 4 hour long M2 physical examination, a session in a decompression chamber and a test flight in a Link Trainer, as well as academics”. On May 16, 1941 AC2 Kingdon, having graduated from No 1 ITS, was struck-off-strength from No 1 ITS and promoted in Rank from AC2 to a Leading Aircraftman (LAC) and his Trade was Airman Pilot. On May 17, 1941 he was taken-on-strength to No 10 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) located at Mount Hope, Ontario. An EFT School provided the candidates 50 hours of basic flight instruction in a simple trainer, such as a Tiger Moth. Elementary Schools were operated by Civilian Flying Clubs under contract to the RCAF and most of the Instructors were civilian. On July 3, 1941 LAC Kingdon, having graduated from the EFTS, was struck-off-strength from No 10 EFTS. Graduates of the EFTS ”Learn to Fly” Program went on to a Service Flying Training School (SFTS). Candidates in the Fighter Pilot stream were sent to the appropriate School.

On July 4, 1941 LAC Kingdon was taken-on-strength to No 1 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) at

Camp Borden, Ontario. Candidates would spend 16 weeks in training, the first 8 weeks was as part of an Intermediate Training Squadron, the next 6 weeks with an Advanced Training Squadron and the remaining 2 weeks at a Bomber and Gunnery School (BGS). Service Schools were Military establishments run by RCAF Personnel. LAC Kingdon spent July 4 to August 29, 1941 training in a Harvard Trainer. The Harvard Trainer Mk IIB was a two seater aircraft, built in Canada and was used as an Advanced Trainer, by the RCAF. This aircraft helped Pilots make the transition from the lowered powered primary trainers to higher performance aircraft. The Harvard Trainer Mk IIB specifications were: length 28′ 11”, wingspan 42′, powered by 1 – 600 hp Pratt Whitney Wasp engine, max speed 180 mph, cruising speed 140 mph, Service height 22,400 feet, range 800 miles.

October 6, 1941 LAC Kingdon amassed the following Flying Training recorded in “hours”:

Aircraft Day Night Instrument Link

Dual Solo Dual Solo Trainer

Harvard 32.30 16.50 4.15 5.45 17.45

Yale 11.10 19.55 2.15

TOTAL 43.40 36.45 4.15 5.45 20.00 15.20

Forwarded

from EFTS* 34.55 25.05 5.30 10.00

GRAND 78.35 61.50 4.15 5.45 25.30 25.20

TOTALS

*Elementary Flying Training School

October 7, 1941 LAC Kingdon was promoted to the Rank of Temporary Sergeant (T/Sgt), paid and his

Trade was Airman Pilot, Special Class and he was awarded the “Pilot Flying Badge”. October 8, 1941 T/Sgt Kingdon was struck-off-strength from the No 1 SFTS at Camp Borden and was taken-on strength to No 1 “Y” Depot at Halifax, Nova Scotia on October 9, 1941. October 22, 1941 he was struck-off-strength from No 1 “Y” Depot to the Royal Air Force (RAF) Trainees Pool; he occupied public quarters and drew Rations. October 23, 1941 Sgt Kingdon embarked Canada at Halifax, Nova Scotia for England. About November 3, 1941 he disembarked at England. November 4, 1941 Sgt Kingdon is taken-on-strength with No 3 Personnel Reception Centre (PRC). November 18, 1941 he was struck-off-strength from the No 3 PRC to No 52 Operational Training Unit (OTU), RAF at Aston Down. February 10, 1942 Sgt Kingdon was struck-off-strength from No 52 OUT, RAF to the No 616 (South Yorkshire) Squadron, Royal Air Force (RAF).

February 16, 1942 he was attached to RAF Kirton-in-Lindsey from the No 616 Squadron (Sqn) RAF. February 18, 1942 Sgt Kingdon was struck-off-strength from the No 616 Sqn RAF to RAF Station Wittering

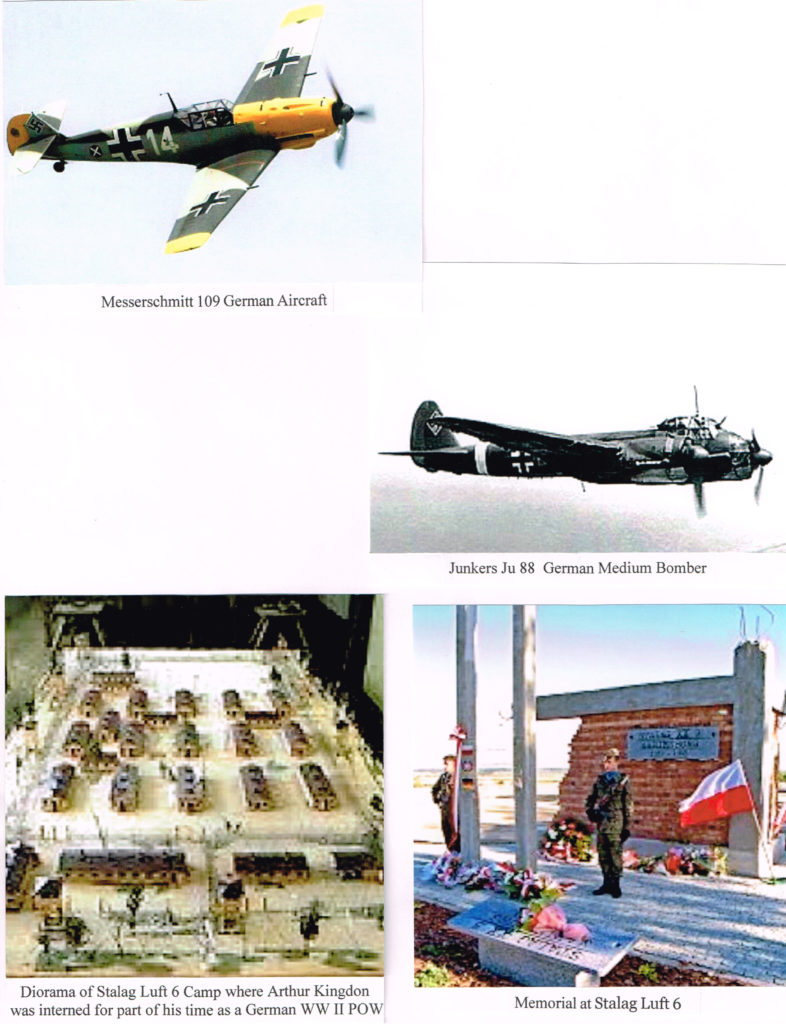

at Cambridgeshire, England pending posting Overseas to Egypt. March 14, 1942 he was struck-off-strength to No 4 PDC from RAF Station Wittering. On March 21, 1942 Sgt Kingdon proceeded to the port of embarkation for posting Overseas (Egypt) with the Draft; he would join No 88 Squadron, RAF. March 23, 1942 Sgt Kingdon left ME for the RAF Training Centre (TC) Almaza, located northeast of Cairo, Egypt. Note that Sgt Kingdon was flying the Hawker Hurricane in Egypt; not the Spitfire. April 7, 1942 Sgt Kingdon was promoted to the Rank of Temporary Flight Sergeant (T/F/Sgt) paid. On June 14, 1942 F/Sgt Kingdon left the RAF TC Almaza, RAF for the No 1 Meteorology Station (METS). Then on June 21, 1942 he left the No 1 METS and returned to the RAF TC Almaza, RAF. June 23, 1942 F/Sgt Kingdon left RAF TC Almaza, RAF for the TC War Depot (WD). Then on July 1, 1942 he left the TC WD for the No 25 Pilot Training Course (PTC). Also on July 1, 1942 F/Sgt Kingdon left the No 25 PTC on transfer to the 33rd Squadron, RAF with a brief statement of his trade qualifications, character and general conduct: “F/Sgt Kingdon is a cool and steady Non-Commissioned Office (NCO) and very keen to fly. He is of excellent character and very popular.” August 19, 1942 F/Sgt Kingdon was on a strafing run 30 kilometres into the desert when a Messerschmitt 109 attacked and hit his aircraft. The Messerschmitt’s bullets had hit the glycol cooling system spraying boiling glycol on his right leg which was badly burned. He was admitted to the No 7 AGH to treat his leg and ankle area. F/Sgt Kingdon was discharged from the Hospital and in September he was back in the air again, strafing enemy installations and equipment.

October 7, 1942 F/Sgt Kingdon was promoted to the Rank of Temporary Warrant Officer 2nd Class (T/WO 2) paid. On October 9, 1942 T/WO 2 Kingdon was on a sortie to be lead by his Wing Commander, he took the Squadron (a Squadron would contain 12 to 24 aircraft) and met his leader at about 2,000 feet. When the formation attacked the Germans were waiting for them; F/Sgt Kingdon took an evasive manoeuver but was struck. Glycol was all over the cockpit and flames started around the instrument panel and the motor quit, he ditched the plane in the Mediterranean Sea and was reported missing (details courtesy of the “Art Kingdon’s Story” by Jon Newton). A while later WO 2 Kingdon is reported as being a Prisoner of War (POW) [M9237]. WO 2 Kingdon’s mission was the Western Desert of Egypt, he was flying on Sortie No 33 and had 62 hours flying. It is believed that he was attacked by a German Messerschmitt. WO 2 Kingdon was moved around a lot until he was interned at “Stalag 1 C in Barth” in June 1943 from where he would have been moved to Stalag Luft 6. [see his Personal History which follows for more details]

Stalag Luft 6 was by far the most northern German WW II POW Camp. On lists with POW Camps it is always indicated as having been open from June 1943 to July 1944, but this camp has a much longer history. It was built in 1939 as Stalag 1C. The first prisoners were of Polish nationality. In 1940 French and Belgian prisoners were brought to the camp and in 1941 also Russian prisoners. It is only in June, 1943 that it became a Stalag Luft 6 for enlisted men, when British and Canadian NCOs (non-commissioned officers) came to the Camp from Stalag Luft I in Barth.

During his Service, P/O Kingdon would have encountered the Messerschmitt Bf 109 single-engine fighter (also known as the Me 109); the Messerschmitt Bf 110 twin-engine heavy fighter/bomber (also known as the Me 110), the Focke-Wulf Fw 190 and the Junker Ju 88, a medium bomber. In the air the Spitfire Mk IX was equal, in performance, to the Me 109 and Fw 190. Often the advantage, in aerial combat, went to which aircraft had the better initial position, numbers, tactics, and Pilot skill.

Notices to WO 2 Kingdon’s parents:

October 20, 1942 “Missing” October 9, 1942 after Air Operations Overseas (Egypt).

November 7, 1942 Authority International Red/Cross/Chief of the Air Staff. Previously reported

Missing, “October 9, 1942 after Air Operations Overseas (Egypt)”. Now reported Prisoner of War and in Dulacluft/German Information.

May 9, 1945 Previously reported “Now reported Prisoner of War and in Dulacluft/German Information”

Now “SAFE” 4 May 1945 in United Kingdom.

On April 7, 1943 WO 2 Kingdon was promoted to the Rank of Temporary Warrant Officer 1st Class (T/WO 1) paid. On April 7, 1944 WO 1 Kingdon was promoted to the Rank of Pilot Officer (P/O) Bomber General List (Br GL) and assigned Service Number J 96325.

On May 2, 1945 P/O Kingdon was liberated east of the Elbe in the Lunenburg Section by the Sixth Airborne Division, USA. May 3, 1945 P/O Kingdon’s discharged was amended on application to a Commission and on May 4, 1945 he arrived in England was taken-on-strength on application to a Commission as amended. Also on May 4, 1945 P/O Kingdon was struck-off-strength to a Non Effective Unit (NEU) No 3 PRC and then was taken-on-strength to No 3 (RCAF) PRC. May 12, 1945 he was granted 14 days Privilege Leave, to visit some family members living in England, to May 25, 1945. On May 30, 1945 P/O Kingdon was struck-off-strength from No 3 (RCAF) PRC to No 1 Repatriation Depot (RD). May 31, 1945 P/O Kingdon was taken-on-strength with the No 1 RD at Lachine, Québec and embarked on the French Liner, Louis Pasteur arriving in Halifax, Nova Scotia on June 7, 1945. June 11, 1945 he was struck-off-strength from the No 1 RD to No 1 Composite Training School (KTS) at Toronto. Also on June 11, 1945 P/O Kingdon was granted 42 days Special Leave to July 24, 1945 and was at home in Lakefield on June 10, 1945. June 12, 1945 P/O Kingdon was taken-on-strength to the No 1 KTS. July 10, 1945 he is reported as being safe – DCL.

P/O Kingdon’s Military File doesn’t contain much detail; the following text is taken from a Newspaper Article by Jessie Doubt who interviewed Arthur Kingdon in Lakefield on June 12, 1945

P/O Kingdon was shot down in combat at El Daba, on the Western Desert of Egypt. Parachuting into the Mediterranean Sea at 4 p.m. on October 9, 1942, he reached the shore at 9 a.m. the next day, alternately swimming and resting in his “Mae West.”

On shore he was taken into custody immediately by Italian soldiers with German NCO’s in charge from El Daba he was flown in a Junkers 52, along with a native of Kenya, also a prisoner, to Dulag Luft at Frankford in Germany. From the Dulag Luft, a Dispersal Camp, he was sent to his first main Camp at Barth, Stalag Luft I. Here the prisoners were quartered 130 in a hut, six to a room. They slept on bunks with “mattresses” of wood wool in sort of a sack affair and were allowed two blankets.

After a year these Prisoner of War (POW) were moved, by train, in a boxcar to a place near Memel (probably Stalag Luft No 6). The journey took five days. There was no room to lie down but they could sit down if everyone co-operated. At Memel the treatment was a little rougher and the food wasn’t even as good as before. After eight months they were again moved, this time to Gros Tiesow. Here they received brutal treatment. As they came out of the boxcars, they were run down the road by the guards with bayonets and dogs. In order to keep ahead the prisoners threw everything away, even their personal kit. It was here PO Kingdon lost his blankets which his mother had sent through the Red Cross.

Pilot Officer Kingdon remained at this Camp from July 1944 until the end of January 1945, when he was sent out on the famous hunger march; marching from February 1, 1945 as the invading Allied Armies advanced, until he was liberated on May 2, 1945.

They were liberated east of the Elbe in the Lunenberg Section by the Sixth Airborne Division, USA. The boys mildly were “more than glad” to be free again. Pilot Officer Kingdon was flown in a C 46 with twenty-five other men to England, arriving south of London on May 4, 1945. From here they went directly to the Canadian Air Force Reception Depot at Bournemouth.

Having two uncles in London and South Hampton, Arthur Kingdon spent a short holiday with them, paid a brief visit to cousins in Blantyne, Scotland, his mother’s hometown and sailed for Canada on May 31, 1945 aboard the French Liner, Louis Pasteur, arriving in Halifax, Nova Scotia last Thursday, June 7, 1945 and home to Lakefield Sunday night, June 10, 1945.

See complete Article in John Arthur Kingdon’s Personal History which follows.

August 8, 1945; information from a Personnel Counselling Report indicated that P/O Kingdon had been a Pilot for 52 months, Overseas 42 months and a POW for 2 years and 7 months. After his release, his chosen career was “Owner/operator of a small Building Supply Business” and he intended to live in Lakefield. P/O Kingdon was discharged on completion of his term of volunteer Service. His future plan is to take over his father’s business.

On October 22, 1945 P/O Kingdon is struck-off-strength from No 1 KTS to the No 4 Release Centre, Toronto. October 26, 1945 upon completion of his Active Service, Pilot Officer John Arthur Kingdon was ”honourably released” from the Royal Canadian Air Force, and was transferred to the Reserve, General Section, Class ”E”. There is no mention as to when P/O Kingdon was discharged from the Reserve.

P/O Kingdon’s Military File indicates that during his service he was awarded the:

1939 – 45 Star;

African Star;

Defence Medal;

Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and Clasp; and

War Medal 1939 – 45.

He also was awarded his Pilot’s Flying Badge.

Pilot Officer John Arthur Kingdon served for a total time of 4 years, 10 months and 8 days: 1 year, 2 months and 24 days in Canada; 1 year and 5 days in England; 23 days Travel Time and 2 years, 6 months and 24 days as a Prisoner of War.

An excerpt from an article in Maclean’s magazine by Barbara Ameil, September 1996:

”The Military is the single calling in the world with job specifications that include a commitment to die for your Nation. What could be more honorable”?

From a clipping from the Peterborough Examiner October 6, 1945:

PO. Arthur J. Kingdon Recalls

Brutality Of Guards

On Return From Hun Prison Camp

BY JESSIE DOUBT

LAKEFIELD, June 12.—(NS) Interviewing Pilot Officer, Arthur Kingdon who returned to his home in Lakefield on Sunday evening one realized with clarity that here was a man with the horrors of two and a half years in a German camp.so deeply embedded in his soul that though time might dim the memory of the atrocities he has witnessed, they would never be completely erased.

Pilot Office Kingdon very reluctantly answered questions.

One felt as if one was probing into a past that; Pilot Officer Kingdon wanted to remember as little as possible.

He was shot down in combat at El Daba, on the western desert of Egypt. Parachuting into the sea at 4 p.m. on October 9, 1942, he reached the shore at 9 a.m. the next day, alternately swimming and resting in his “Mae West.”

Taken To Reich

On shore he was taken into custody immediately by Italian soldiers with German NCO’s in charge. From El Daba he was flown in a Junkers 52, along with a native of Kenya, also a prisoner, to Dulag Luft at Frankford in Germany.

Praises Red Cross

Questioned as to the food situation at this camp he said he had highest praise for the Red Cross parcels. PO Kingdon had the sufficient to eat along with the Red Cross without whose aid he intimated he would not have survived on the meager fare served at the various camps. At that he said he was fortunate in being sent to the better camps. From Dulag Luft, a dispersal camp, he was sent to his first main camp at Barth, Stalag Luft I. Here the prisoners were quartered 130 in a hut, six to a room. They slept on bunks with “mattresses” of wood wool in sort of a sack affair and were allowed two blankets.

Queried as to what time they arose and what time meals were served, he indicated hours were uncertain, except that they paraded at 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. for roll call, and depended largely on Red Cross parcels for food. They were not forced to work, except to carry their own fuel and whatever foodstuffs were available, but were never allowed out of the compound. The guards here were, to quote PO Kingdon “Reasonable enough.”

Tries To Escape

Five or six of the boys escaped by digging tunnels but were soon captured and returned. The flier said he spent considerable time digging tunnels but didn’t succeed in getting out.

After a year these boys were moved by train in a boxcar to a place near Memel. The journey took five days. There was no room to lie down but they could sit down if everyone co-operated. The guards, two inside and two outside, made hot cocoa occasionally on the trip — consuming most it themselves. They handed out a bit of bread from time to time as the spirit moved them.

At Memel the treatment was a little rougher and the food wasn’t even as good as before. The guards shot and killed two American airmen who tried to escape. The boys worked hard and made a skating rink to have only one skate with skates supplied by the Y.M.C.A. before the thaw came.

They had a church services on Sundays conducted either by two Protestant padres, one a civilian internee from the Channel Islands, or a Roman Catholic padre.

The Red Cross supplied them with a piano and musical instruments, all of which had to be left behind each time they were moved on and then they had to start collecting equipment all over again.

Chased With Bayonets

After eight months they were again moved, this time to Gros Tiesow. Here they received brutal treatment. As they came out of the boxcars, they were run down the road by the guards with bayonets and dogs. In order to keep ahead the prisoners threw everything away, even their personal kit. It was here PO Kingdon lost his blankets which his mother had sent through the Red Cross.

Asked as to conditions at this Camp he said they weren’t very pleasant but he refused to enlarge on it except to say that the treatment was worse than at any of the other camps. One American chap was shot and killed jumping out a window. Officer Kingdon remained at this camp from July until the end of January, when he was sent out on the famous hunger march — marching from February the first as the invading Allied armies advanced until he was liberated on the second of May.

20 Miles A Day

The hunger march was by far the worst part of his imprisonment. The boys were forced to march as much as thirty miles a day, averaging about twenty. The guards marched too but they hadn’t any packs to carry. Occasionally they were given a few potatoes and a bit of bread to eat.

Those who were physically unable to go on were taken away in farm carts, a few of whom the boys saw later in camps along the roads, but they didn’t know what happened to the others.

On the last two weeks of the hunger march Red Cross lorries were able to locate them and brought them food.

On May 2 they were liberated east of the Elbe in the Lunenberg section by the Sixth Airborne Division. The boys mildly were “more than glad” to be free again.

Flown To England

Pilot Officer Kingdon was flown in a C 46 with twenty-five other men to England, arriving south of London on May 4. From here they went directly to the Canadian Air Force Reception Depot at Bournemouth.

Having two uncles in London and South Hampton, he spent a short holiday with them, paid a brief visit to cousins in Blantyne, Scotland, his mother’s home town, and sailed for Canada on the French Liner, Louis Pasteur, arriving in Halifax last Thursday and home to Lakefield Sunday night.

Asked as to what impressed him most on his arrival in Canada, he said it was the “naturalness” of Canadians in comparison to Europeans. He said it was very refreshing, the Canadians had given them a royal welcome and he was very glad to be home.

Likes R.C.A.F.

Pilot Officer Kingdon’s plans for the future are uncertain. He said he would like to remain in the air force but his family thought he had been in long enough.

He was welcomed home by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. O. E. Kingdon; his sister, Leona, Mrs. George Graham; his brother, Melville, both of Lakefield; his brother Bob, his twin sister, Jean, Mrs. Ernie Nutt of Peterborough; and his fiancée, Miss Dorothy Clydsdale from Westwood. She is a teacher at the Rifle Range School in Peterborough.

A YEAR IN THE AIR OVER ROMMEL’S DESERT – ART KINGDON’S STORY

The Second World War lasted for only six years, but it seemed like an eternity. More than 42,000 Canadians had given their lives on land, sea and in the air and more than 53,000 had been wounded by 1945, when it ended.

The Allies prevailed, but for a time it seemed Hitler might conquer them and one of the most decisive, hard-fought actions was in Libya, North Africa, where Germany’s general, Erwin Rommel – the wily Desert Fox – was driving his seemingly invincible Deutsche Afrika Korps hard at the Suez Canal in Egypt.

Rommel was defeated at el Alemain and contributing to his downfall was a tiny desert air force, operating from makeshift bases deep in the Sahara. Ill equipped and flying in what were frequently near impossible conditions, it constantly harried Rommel’s advance, costing him irreplaceable material and troops. And time.

One of the men flying the planes was Royal Canadian Air Force Sergeant Arthur “Art” Kingdon, a fighter pilot from Peterborough.

It was 1940 and Art Kingdon was working at his father’s barrel heading and shingling factory in Lakefield, learning the trade. But there was a war on and Art knew it, and like thousands of other young Canadians, he wanted to do his bit.

Piloting a fighter aircraft seemed a good way to get into the action so at the end of June, he was at an RCAF recruiting office in Ottawa where he was told yes, there might indeed be a role for him in the air. But as an air gunner, not a fighter pilot.

“I said, ‘The Hell with That’ “, Kingdon recalls. “One way or another, I was going to be a pilot!” Five months later he was signing on the dotted line for initial pilot training in Toronto. There, “They put a bunch of us in a decompression tank and gave us math problems to solve,” Kingdon says, laughing. “When we’d reached the equivalent of about 25,000 feet, I and another guy were the only two left so I guess they figured we’d do as fighter pilots.”

He won his wings as a sergeant pilot on October 9, 1941. And October 9th would prove an extremely significant date for him. Kingdon qualified on Spitfires but wound up in Egypt, attached to the RAF’s 88 Squadron, which was operating from forward airfields in Egypt.

“And what a let-down that was,” he says, “going from a Spitfire to a Hawker Hurricane.” At first, the Hurricanes had four cannons, says Kingdon, “But if you pulled up and fired them, the recoil could knock you into a spin. So they took two off. That helped, but of course it also cut the fire-power in half.”

Life was hard. Living in tent cities, Kingdon and his fellow fighter pilots flew sortie and sortie against Rommel’s troops and bases and when they weren’t doing that, they were training. Even at night they got little rest, frequently having to dive into slit trenches dug conveniently outside their tents to escape strafing attacks from German Ju-88s. Then there were the scorpions, the heat and the ever-present flies. And the sand.

“It got into everything,” says Kingdon, “including our bully beef stew”. The flies were even worse. “At one landing ground beside a native camp,” he recalls, “they were so bad we had two tin plates – one for our food and one to cover the first plate. And the flies would follow each fork-full of food into our mouths.” Kingdon, nick-named Pop, was flying Hurricanes into enemy territory in Libya. In August 1942 he was on a strafing run 30 kilometres into the desert when a Messerschmitt 109 bounced him.

“Our Hurricanes were no match for the 109,” he says. “The Hurrie could out-turn it, but that was about all. On top of that, we were new pilots who’d only just come out of training”. “The 109 came at me as I was trying to meet him. He was coming down and I was going up and he beat me by about a second”. “He fired and I went into a tight spin, so tight I almost couldn’t get out,” he says. “But I finally got my kite under control and flew it back.”

“There were specially graded strips built close to our lines for damaged aircraft and I landed on one of those. My instruments were shot to hell and I couldn’t tell if my wheels were down. But they were, thankfully, and I got down without crashing.”

He’d manage to land safely, but the 109’s machine gun bullets had pierced the Hurricane’s glycol cooling system and boiling glycol sprayed onto Art’s right leg. He was badly burned and out of action until September, when he was back in the air again, strafing enemy installations and equipment. Then, on October 9, 1942 – a year to the day after Kingdon had received his pilot wings – he was shot down again.

He’d just returned from a 48-hour pass in Alexandria when he was told his wing commander wanted him as his No. 2. “His kite was at another field,” Kingdon says. “I was ordered to take the squadron and meet up with him so he could take over the lead. I was also told to make sure I took a Mae West (Life preserver) and if I got hit, to go out the same way I came in – over the sea.”

Kingdon and the other Hurricanes met the wing commander at about 2,000 feet and, “he immediately took us down to 15 or 20 feet, I had a bad, bad feeling”. This was supposed to be a surprise to the Germans, but they could see us coming for miles. “Two days earlier, the Germans had had heavy rain on their side of the lines and according to one of our recce (reconnaissance) kites, the 109s were bogged down on their field”. “But as we came in from the sea and broke over a cliff, about 100 feet high, on the coastline, I could see the 109s circling. And there was a solid wall of ground gunfire.”

“I yanked back on the stick to try to climb over the cone of ground fire and for a second, I thought I’d made it. But then I heard a loud bang and the windscreen was instantly covered with glycol. I pulled up to miss the guys behind, made a flat turn and headed back the way I’d come. “I thought I could maybe make it back to opposite our lines and crash-land on the beach. I really didn’t want to go into the water because the older Hurricanes had two large cooling scoops under the belly and I imagined what they’d do if I hit the sea.”

“I pulled my RT (radio) cord, slid the canopy back and prepared for the worst. Then I saw flames curling around the instrument panel so I had to make a fast choice – burn or swim. But it wasn’t really a choice because right then, my motor quit.” “So I hit the water and, as I’d dreaded, the scoops caught, somersaulting my plane onto its back and it sank – upside down.” “Not to worry, though. I hit my shoulder harness a good whack, got my feet on the seat, gave a mighty push downward, rolled out over the edge of the cockpit – hoping nothing would get caught – and popped out like a cork from a bottle.” “But I’d forgotten to release my parachute and I was floating with my ass in the air and my head underwater, a situation which I quickly corrected,” Kingdon says dryly.

“Then I started to worry about my Mae West. When it was issued, it included a small ring that held the pressure bottle in place, but I’d never tightened it. I was afraid that if I pulled the lever to release the pressure, it would shoot the bottle out. I cursed the fact that I hadn’t kept track of my chute.”

“As the afternoon wore on, the sea became choppy and I was swallowing water, so I blew air into the vest. It helped, but I was getting tired. I’d swim for a while, and then floated on the vest but it didn’t have enough air in to and in desperation, I tried the bottle. It filled out and held up. Someone was looking after me!”

At about 10 p.m., Kingdon says, bombers flew overhead and hit the German field whose planes were supposed to have been bogged down. “There was a new moon which shone a silver streak across the water and suddenly, a large, dark fin shot through the water,” said Art. “I started to kick and thrash before I realized that was the worst thing I could do if it was a shark.” “It stayed with me and as I swam, I kept hitting it with a hand or foot.” “I kept swimming and resting and swimming and resting and I was very surprised when the sun came up. But in the light, I could see the fish still swimming around me – and it wasn’t a shark; it was a dolphin!”

“And I could see land, although it was a long way off. I kept going, with the dolphin keeping me company, and eventually, I could see men on top of the cliff we’d flown over the day before.” At this point, Kingdon estimates he had been in the water for about 17 hours. The men on the cliff were three Italians. “They were motioning me to swim on up the coast to where the land sloped down to a small beach. But I was in no shape to swim that far – it was about half a mile away – and I decided to swim to a boulder I could see at the base of the cliff.”

“When I reached it, every time a swell came up it would lift me and I’d grab for it, but it was too slippery to hang on to and after several tries, I gave up. “In the meantime, the boys on the cliff were getting organized. They’d assembled a bunch of climbing equipment and they let two men down to a ledge and one of them let the other down to where I was”. “When I washed up, he grabbed my hand and pulled me aboard the rock.”

“Grinning, he pulled me up – to spend the next two-and-a-half years as a prisoner of war in a German camp.” Kingdon spent about a year at Barth on the Baltic across from Sweden, another year at a camp in Lithuania and his final six months as a POW near Peenemunde, where the Germans had developed the V2, among other deadly rocket-propelled weapons.

But the War ended and Kingdon made it home, where he married his fiancée, Dorothy. “After four-and-a-half years, she was still waiting for me, even though half the time she didn’t know if I was dead or alive.” he says. And his wartime experiences hadn’t killed his love of flying. As soon as he could, he got a civilian license and spent many happy years flying around Canada and the United States.

Kingdon is now into his 80s but he’s still going strong. He has two children – Randy and Kimberley – and six grandchildren, and although his sight is failing, he still spends some of his time at Kingdon Lumber, the Lakefield firm he founded on the same site as his father’s business.

The above article was written by Jon Newton, Special to the Peterborough Examiner, August 27, 2002.

PERSONAL HISTORY

JOHN ARTHUR KINGDON

John Arthur was born June 25, 1917 in Peterborough, Ontario, the son of Orville Edward Kingdon and Robina Kirkwood. John Arthur went by the nickname “Art”. Art was fluent in English and could read and write French fairly well.

Art enjoyed many sports: Badminton; Swimming, Baseball, Rugby, and Track & Field extensively plus Hockey and Tennis moderately. He did general worked in a Barrel Heading and Shingle Factory from 1935 to 1939. He left this work to return to High School to get an honour matriculation and with the intention of going on to College.

In an interview he was asked what Special Qualifications or Hobbies useful to the RCAF he had; he responded that he had done a lot of woodworking, especially on wood-lathes. Art also stated that he intended to take a course in flying to get a private pilot’s licence.

John “Arthur” Kingdon married Dorothy Margaret Clysdale on July 5, 1945. They had two children John Randolph (Randy) and Kimberly “Kim” Sue Kingdon. Randy Kingdon married Barbara Stutley on September 19, 1970 in St. John’s Anglican Church in Ancaster, Ontario. They have three children: Janis Kingdon married Corey Spalding; Bryan Kingdon married Mary McEachem and Michael David Kingdon married Emily Susanne Barr. Kim Kingdon married Donald Dyck on July 18, 1981 and they have three children: Mya Dyck married David Breukelaar; Kevin Dyck, married Jessica Zantingh and Rachel Dyck.

John Arthur Kingdon was the owner of Kingdon Lumber in Lakefield, which was started by his father Orville Edward Kingdon. The business was then owned and operated by Art and his brother Melville “Mel”; Art later bought out Mel’s interest in the business. Kingdon Lumber is now owned and operated by his son-in-law, Don Dyck, husband of Kimberly Kingdon. Art also was the owner of Kingdon Homes and built many homes in the Peterborough and Lakefield area. From 1961 to 1962 Art was Reeve of the Village of Lakefield.

John Arthur Kingdon passed away on December 27, 2003 and Dorothy Margaret died July 16, 2011; both are interred in Little Lake Cemetery in Peterborough.

THE JOHN ARTHUR KINGDON FAMILY OF LAKEFIELD

John Arthur Kingdon’s paternal great grandparents were William and Theresa Kingdon. His maternal great grandparents were John and Lydia Rook.

John Arthur Kingdon’s paternal grandparents were George Samuel Kingdon, born December 15, 1842 and Sarah Elizabeth Rook born on July 26, 1849. They were married in Newburgh, Lennox & Addington County on May 17, 1870. They resided in Peterborough and George operated a barrel & shingle factory on Barnardo Avenue in Peterborough. George & Sarah had six children: Clara, born about 1873; Harriette Emma, born June 30, 1876; Arthur Rook, born November 12, 1878; Richard Henry, born November 10, 1880; Edward Norman, born October 19, 1884 and George Stanley, born September 3, 1889, married Florence M. Doughty on September 4, 1909. Note: Edward Norman was the birth name of the child born on October 19, 1884 and apparently his name was changed to Orville Edward.

Sarah Elizabeth passed away on March 3, 1930 and George Samuel died on September 6, 1930; both are interred in Little Lake Cemetery in Peterborough.

John Arthur Kingdon’s maternal grandparents were Robert Kirkwood and Jean Goldie Creighton.

John Arthur Kingdon’s father Orville Edward Kingdon born October 19, 1884, was first married to Etta Maud Johnston, born March 21, 1885 in Manvers Township. They were married in Otonabee Township on May 9, 1906. Orville, a cooper, was living in Peterborough, Ontario and Etta Maud was living in Otonabee Township. Orville and Etta had two children: Melville Orville, born November 28, 1906 married Eva Helen Hill and Leona Maud Kingdon, born May 6, 1909, married George Henry Graham. Both children were born at 13 Hilliard Street in Peterborough.

Unfortunately, Etta Maud became ill with tuberculosis in 1909 and was moved to the King Edward Sanatorium in York; she was seen by Dr. W. J. Dobbie from February 25 to May 3, 1910 when she passed away leaving Orville with a very young family. In April 1911 Orville was living with the Ray family in Peterborough; Leona was a boarder in Mrs. W. J. Doughty’s house at 862 Water Street, Peterborough and Melville Orville was not located.

John Arthur Kingdon’s parents were Orville Edward Kingdon, born October 19, 1884 and Robina Kirkwood, born September 12, 1880 in Blantyre, Scotland. Orville & Robina were married in Peterborough, Ontario on October 6, 1911 made their home at 28 Barnardo Avenue in Peterborough. Orville & Robina had three children: Robert William, born September 11, 1912, a barber; and twins John Arthur and Jean Goldie Creighton, born June 25, 1917. Jean was a nurse and married Ernest “Ernie” Calvin Nutt in November 1945 and lived in Mount Albert until their divorce. Jean later married Joseph “Joe” John Nicholls and they lived in Lakefield.

Orville Edward Kingdon died October 26, 1958 and Robina died on April 7, 1956; both are interred in Little Lake Cemetery.