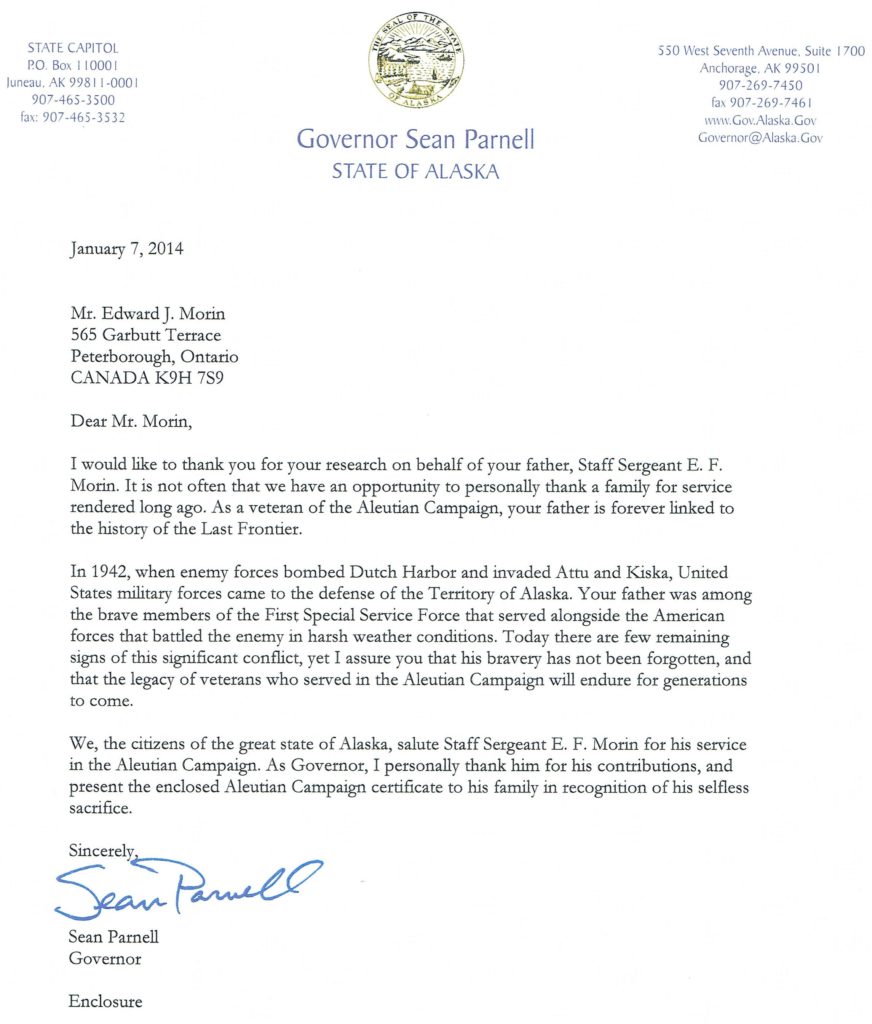

MILITARY HISTORY

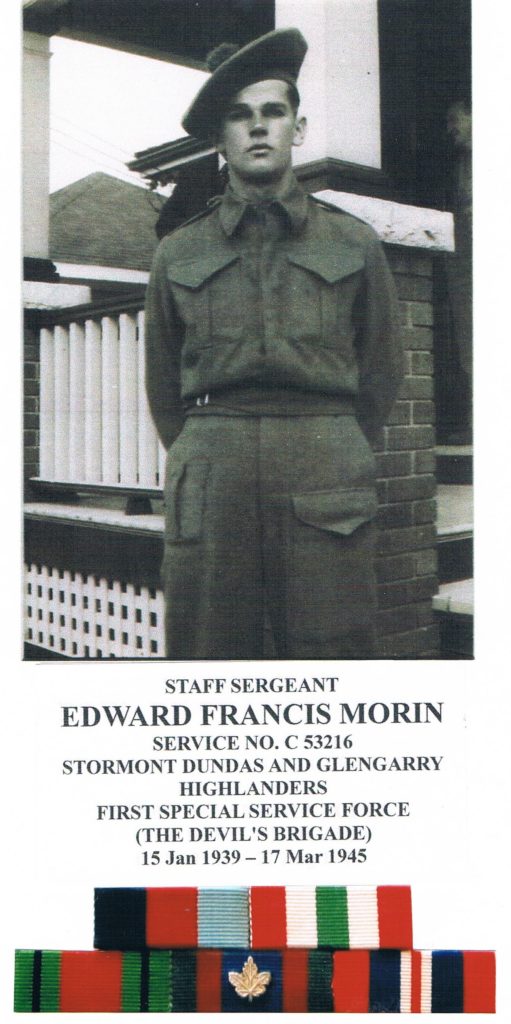

Staff Sergeant Edward Francis Morin – C 53216 — ACTIVE SERVICE (World War II)

Edward Francis Morin was 21 years, 3½ months old when, as a single man, he enlisted in Peterborough, Ontario on July 3, 1940 with the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders (SD&GH), Active Force (AF). Edward Francis stated that he was born in Peterborough Ontario on March 15, 1919 and indicated that he had no previous military experience. His previous employment was listed as a woodworker. Edward Francis was 5′ 8½” tall, hazel eyes, brown hair and weighed 145 pounds. He lived in Lakefield, Ontario and his next-of-kin was listed as Joseph Morin, his father, living in Lakefield Ontario. Edward Francis Morin was assigned the rank of Private (Pte) and Service Number C 53216 with the 1st Battalion, Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, Active Force – Canadian Infantry Corps. He was assigned to D Company, 1st Battalion.

Pte Morin’s records don’t show details for the period from enlisting (July 3, 1940) to November 6, 1940 other than a move to Kingston, Ontario and a promotion announcement. These 4 months would have been used for Basic and Advanced Training which would include marching, military organizations, rifles and machine guns, grenades, mortars, rocket launchers, defensive and offensive tactics, etcetera plus Military Law. Initially this training was probably carried out at Peterborough Ontario until September 4, 1940 when the SD&GH moved to Kingston Ontario. Pte Morin was promoted to Acting Lance Corporal (A/L/Cpl) on October 23, 1940. On November 6, 1940 Pte Morin and the 1st Battalion SD&GH moved to Lansdowne Park in Ottawa Ontario for Bren gun training.

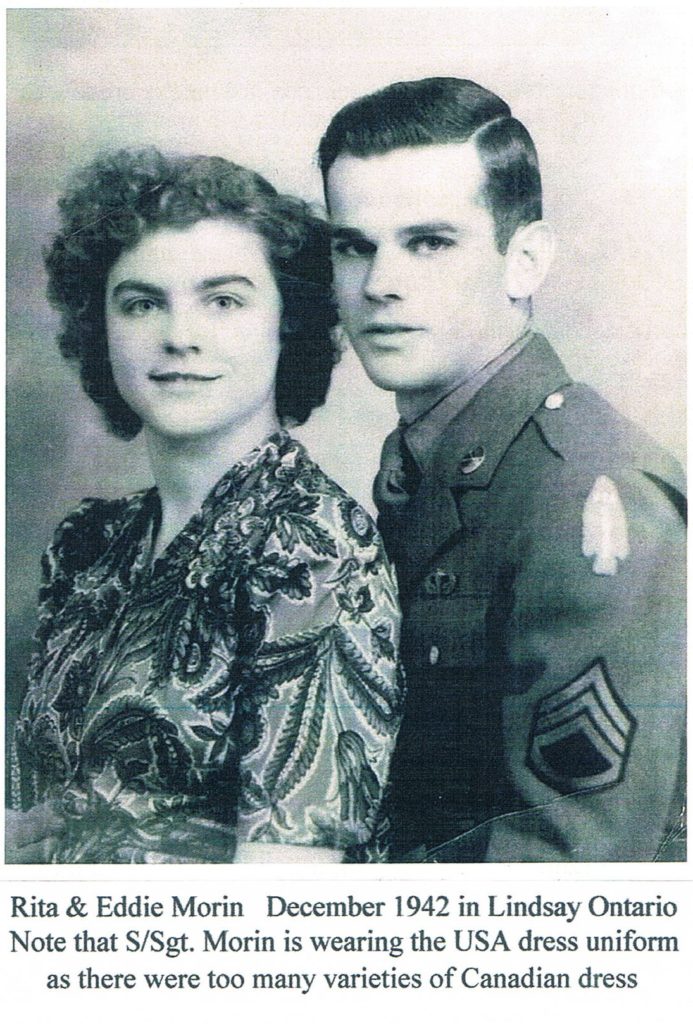

A/L/Cpl Morin was granted leave for December 27, 1940 to January 14, 1941, as authorized by Ottawa. On January 7, 1941 he was also granted permission to marry and married Rita Frances Kelbrick, on the same day, in Lindsay. In January 1941 the 1st Battalion was moved to Debert, Nova Scotia for further training prior to being shipped overseas. January 16, 1941 Pte Morin changed his next-of-kin due to his recent marriage. His new next-of-kin was given as Mrs. Rita Morin, wife, 10 Glenelg St. E., Lindsay Ontario.

While stationed at Camp Debert A/L/Cpl Morin was Absent Without Leave (AWOL) from 0630 hrs. April 15, 1941 to 1950 hrs. April 16, 1941. For this misadventure he was reverted to the rank of Private and awarded forfeiture of 2 days pay. Pte Morin’s records don’t show details for the period from January to July 1941, however, additional training and practice on all weapons at their disposal would have taken place.

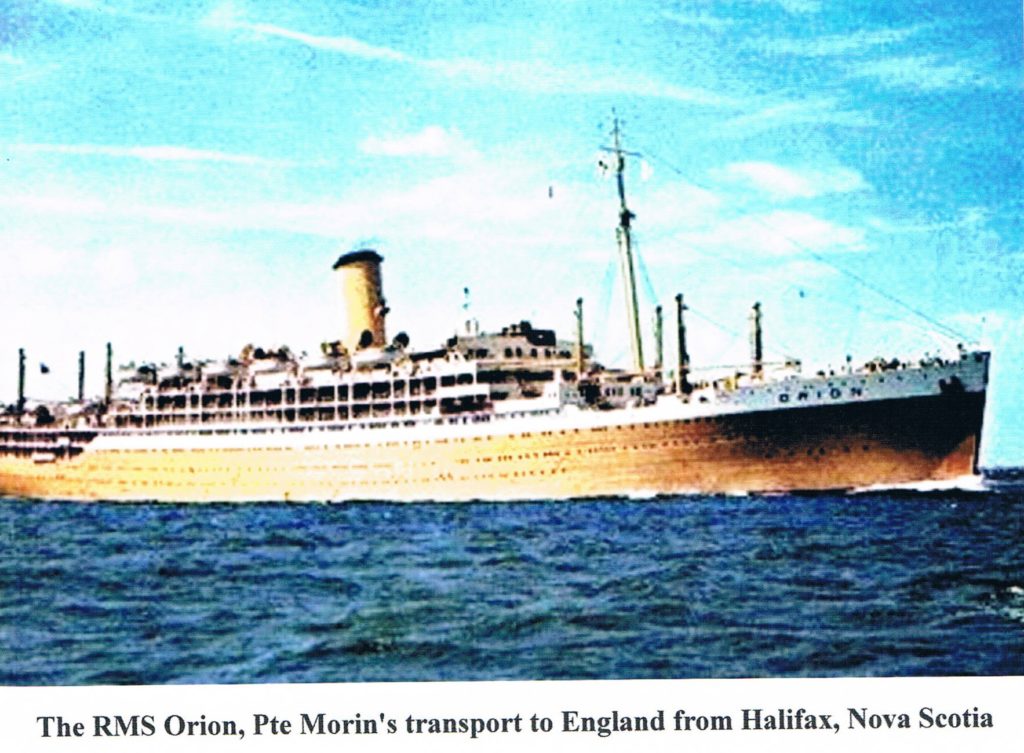

On July 21, 1941 Pte Morin was struck-off-strength from the Canadian Army (Canada) and embarked from Halifax, Nova Scotia aboard the RMS Orion for the United Kingdom (UK). On July 22, 1941 he was taken-on-strength from the Canadian Army (Canada) to the Canadian Army (Overseas) as a member of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, Aldershot, England. July 31, 1941 Pte Morin and his Unit disembarked at Avonmouth, England. A week later he was granted 5 days Landing Leave (with Travel Warrant) from August 7 to 11, 1941. There is no record of activities for the next 7 months, however, Pte Morin was granted his 1st Privileged Leave (with Travel Warrant) from November 14 to 21, 1941. During this 7-month period he would have been doing duties and lots of training.

Pte Morin had a Performance Rating on February 19, 1942 by Major H. Mason, Officer Commanding (O/C) D. Company. Results of this are as follows: his section work history with the 1st Battalion, Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, D Company, was completely satisfactory. He joined the Service due to a sense of duty and was definitely Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) material. Recently he was offered a promotion but refused because he has lost interest in the Infantry. Pte Morin intended to enlist in the Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA) but was switched to the Infantry. Now he wants to transfer to the RCA where he feels his interest would be revived and he could do a better job. He seems to be very ambitious and anxious for promotion in the right branch of the Service.

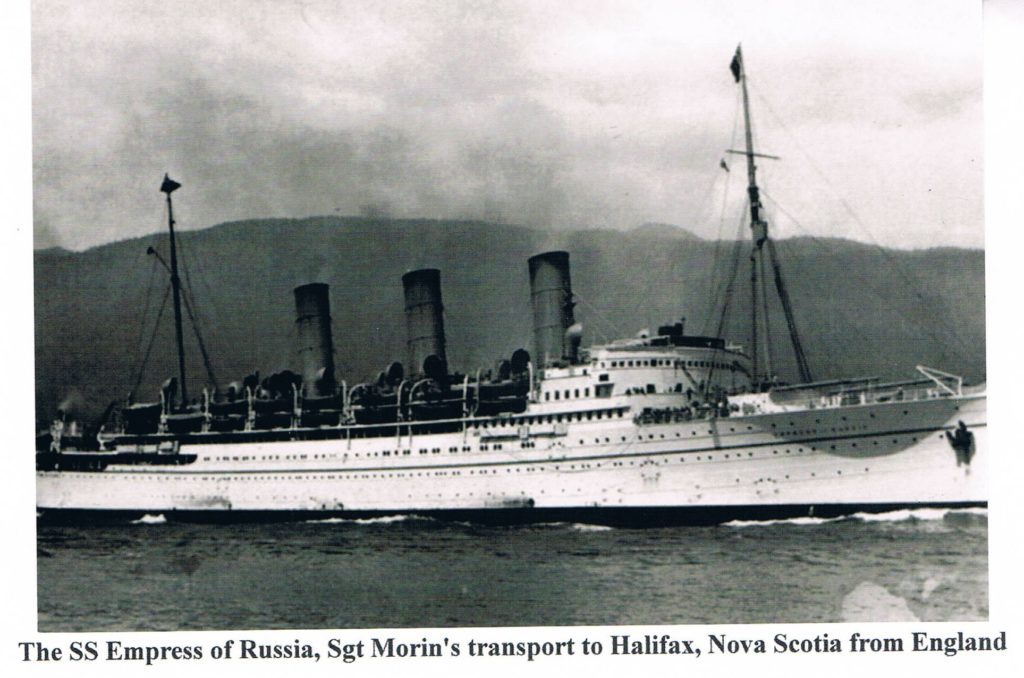

On March 19, 1942 Pte Morin was struck-off-strength to the No 1 Non-Effective Transit Depot (NETD) from the SD&GH. Note; all of the time not specified for the previous 7 months would have been utilized for training and retraining. Practice makes perfect! On March 20, 1942, Pte Morin was taken-on-strength to No 2 Prisoner-of-War (POW) No1 NETD from the SD&GH. March 21, 1942 he was posted to No 2 POW Escort Detachment, No 1 NETD and attached for all purposes (fap) to the Pioneer Corps P/W Wing (British Army). On March 23, 1942 Pte Morin, on-command from Canadian Army Orders, is struck-off-strength from No 1 NETD. He embarked about March 28, 1942 aboard the SS Empress of Russia from the UK, as part of a POW Security Detail, for duty to No 3A District Depot (DD) Kingston, Ontario. April 1, 1942 Private Morin was promoted to the rank of Sergeant (Sgt).

Sgt Morin disembarked at Halifax, Nova Scotia on April 7, 1942. It was stated that Sergeant Morin’s return from 8 months duty in England was as a small arms instructor. April 7, 1942 he was struck-off-strength from the Canadian Army (Overseas) and taken-on-strength to No 3A District Depot (DD) Kingston, Ontario having returned from Overseas for duty. For record purposes; with effect from (wef) March 26, 1942 for duty, discipline, quarters & rations; wef April 9, 1942 for pay and wef April 2, 1942 is posted to “A” Wing, No 3A DD Kingston.

Sgt Morin’s Military Records do not specify what action and training he undertook over the next 9 months other than becoming a parachutist. He was with the King’s Own Rifles of Canada for a short time as a Small Arms Instructor. The new Unit that he volunteered to join, the First Special Service Force, required everyone to become experts in weapons, hand-to-hand combat, parachuting, rock climbing, skiing, explosives and demolition, and conditioned to persevere in severe weather conditions. They had to become the very best in the world at guerrilla/commando style warfare. Hence, it is likely that his training supported these goals. April 30, 1942 Sgt Morin is struck-off-strength from No 3A DD on transfer to No 12 DD, Regina. Saskatchewan. May 1, 1942 he is taken-on-strength to No 12 DD for all purposes on transfer from No 3A DD, Canadian Army Active (CAA), Kingston, Ontario.

On May 3, 1942 Sgt Morin was transferred from No 12 DD to the King’s Own Rifles of Canada (KOR of C), Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. Then, on May 4, 1942 he was with the King’s Own Rifles of Canada fap in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan.

Sometime in June/July 1942 notices were posted in barracks for volunteers. Contrary to the Army warning spread throughout all ranks “Never volunteer for anything.” Sgt Morin put his name on the list, as did 85 others. They discovered that it was to train and serve in a newly created special force composed jointly of Canadian and American soldiers. Canada had said they would only send their “elite”. They were intensely screened for intelligence, strength, and ferocity. Medical and IQ tests reduced the number to 26. After personal interviews they were left with only 16, one of which was Sgt Morin. He was a mortar-man and an Infantry man well versed in small-arm weapons. He completed courses in American weapons, skiing, Junior Leader’s Course and demolitions.

On July 29, 1942 Sgt Morin was posted from the King’s Own Rifles of Canada to Serial 1054 at Terrace British Columbia effective (eff) July 30, 1942. He was also attached to A16 Infantry Training Center (ITC), Calgary Alberta, fap. Then, on August 5, 1942 he ceased to be attached except for pay and the next day, August 6, 1942 he ceased to be attached for pay too.

NOTE: In Canada the two main gathering points for those Canadian volunteers joining the First Special Service Force (FSSF) were Ottawa, Ontario and Calgary, Alberta. It is believed that Sgt Morin was attached to A16 ITC while he was waiting for transit to Montana, USA.

Sgt Morin reported August 7, 1942 for selection to the 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion (later to be named the 1st Special Service Battalion, however, both designations were for Canadian administration purposes only) and was accepted by National Defence Headquarters (NDHQ), Ottawa. August 8, 1942 Sgt Morin reported to an old abandoned Base in Montana, USA called Fort William Henry Harrison, located near Helena, Montana. This is the base where the majority of the arduous training took place. This is also where the First Special Service Force (FSSF) was developed; the men in the FSSF were referred to as “Forcemen”. Sgt Morin was taken on strength from A 16 ITC fap except for Rations and Quarters (R & Q) effective August 7, 1942; he was entitled to draw parachutist pay at 75¢ per diem. Sgt Morin was a member of the 1st Regiment, 1st Battalion, 3rd Company of the FSSF.

PLEASE NOTE: The text about the history and exploits of the First Special Service Force following was gleaned from multiple sources. The vast majority of the information was kindly provided by Edward “Ted” John Joseph Morin, eldest son of Staff Sergeant Edward Francis Morin. Many thanks to Ted and all other sources who have provided data which is not included in S/Sgt Morin’s Military Records.

The ensuing 6 months have no entries in S/Sgt Morin’s Military Records. The First Special Service Force’s keystone in the combat missions to come was versatility. This versatility came about as a result of the training they would undergo. To say the training was intense is an understatement. Physical conditioning was used to both upgrade the endurance of the Forcemen but also to weed out individuals who were not up to the task. On another level, this level of training would improve and increase the survival possibilities of the Forcemen in the upcoming planned operation. The Forcemen double-timed between each training session, which began at 4:45 a.m. each morning and ended at 9:30 p.m. Four nights of the week Forcemen attended a lecture on some aspect of warfare. They engaged in daily regimens of callisthenics, obstacle course, treks on “muscle mountain” and long marches. They undertook regular 20-mile marches with 60 lb packs and long wooden poles. In the spirit of competition these marches were often conducted between Regiments. For instance, a 60-mile march course was laid out to see which Regiment could march it the quickest. Forcemen were trained in hand-to-hand combat, parachute jumping, weapons (both U.S. and German), rock climbing, skiing, cold weather fighting, amphibious landings and demolitions.

As far as weapons were concerned, Force weaponry was to include: the V-42 Stiletto Knife; 45 calibre Pistol; Thompson submachine gun; M 1 Garand 30 calibre rifle; Browning light machine gun; Browning automatic rifle; Johnson light machine gun; rocket launcher (Bazooka); 60 mm mortar and portable flamethrower. They were also equipped with the new Ryan’s Special (RS) explosives. The Forcemen were required to “qualify” in the use of all of these weapons.

Upon completion of the parachute training the men were issued their silver jump wings, which they affectionately referred to as “the buzzard claws”. On August 18, 1942 Sgt Morin qualified as a parachutist at Helena, Montana but was authorized for parachutist pay August 7, 1942 due to prior qualification in Canada. On October 28, 1942 Sgt Morin was promoted to the rank of Acting/Staff Sergeant (A/S/Sgt). January 28 1943 A/S/Sgt Morin qualified as Staff Sergeant Morin (S/Sgt). Being a S/Sgt helped equalize the pay differences in the ranks — but it still paid $2.50 less a month than the $1OO American Private.

Skiing training was completed under Norwegian Army Instructors. As far as skiing training was concerned S/Sgt Morin was known as “the trail blazer” for his prowess on skis. It is also worth noting that skiing training took place well away from the Base, where the men slept overnight in boxcars, with temperatures reaching minus 35° to minus 45°F. One Forcemen would relate that the Instructors would have us strip to the waist, in these temperatures, and have us rub snow on the back of the Forcemen in front of us. The idea was to get us use to the cold.

Training mishaps were regular occurrences, with strains, sprains, and sore feet. Based on the realistic nature of the hand-to-hand combat, including knife fighting, there were also the occasional knife and bayonet wounds. In the case of serious injuries such as broken limbs, the individual was immediately returned to his original Unit.

On April 15, 1943 the First Special Service Force (FSSF) [that always included the 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion; which a month later was renamed the 1st Canadian Special Service Battalion, USA] moved to Norfolk Virginia, USA for amphibious training. Then the FSSF moved to Camp Bradford, Virginia. On May 15, 1943 the 2nd Canadian Parachute Battalion adopted the name “1st Canadian Special Service Battalion”, USA. On May 24, 1943 the FSSF moved to Fort Ethan Allen, Vermont. On July 9, 1943 the FSSF embarked at San Francisco, California USA and 15 days later, on July 24, 1943, they disembarked at Amchitka Island in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska USA.

The First Special Service Force’s initial assignment would be to lead the invasion of Kiska Island. The 1st Regiment was to be the lead Unit. On August 15th, 1943, rafts emerged from the cold fog and the men aboard them fought the currents, paddling their way to the rocky coast of Kiska Island to surprise the Legion of Japanese defenders, who according to intelligence sources, were entrenched there. The same sources indicated that Kiska Island was defended by a Japanese Force of 12,000.

Up against the 12,000 Japanese defenders, in the first wave would be the 1st Regiment with a total combat strength of 32 officers and 385 enlisted men. The mission was to secure and mark landing areas, seize the ridge lines and pave the way for the first wave of the invasion Force. But the Forcemen never found any Japanese. Although the Forcemen had not been in action, the Kiska Island operation was considered a successful dry run. Almost one month after arriving, August 22, 1943, S/Sgt Morin’s Unit embarked at Amchitka Island and 10 days later, on September 1, 1943 they disembarked at San Francisco, California USA.

They returned to Fort Ethan Allen, Vermont on September 9, 1943 and S/Sgt Morin was granted leave from September 9 to 14, 1943 to see his newborn son, Edward “Ted” John Joseph Morin, born September 9, 1943. An extension of leave to September 18, 1943 was granted this day. Following his leave S/Sgt Morin’s Unit embarked at Newport News, a port in Virginia, USA aboard the Empress of Scotland (was the Empress of Japan) on October 27, 1943 and headed for Morocco, North Africa. Nine days later, November 5, 1943, the First Special Service Force (FSSF) disembarked at Casablanca, Morocco.

On the trip by rail from Casablanca to Oran an interesting occurrence with wine took place. A train carrying wine in casks parked right beside the coaches carrying the Forcemen; that was just too much to resist. Many later sipped it from their helmets. The train travelled 300 miles on the last land portion of the trip from Amchitka Island in the Aleutian Islands to Italy, where the Brigade saw action. Eight days after leaving Casablanca, November 13, 1943, S/Sgt Morin embarked at Oran Algeria and headed for Italy where they disembarked at Naples 5 days later on November 18, 1943.

November 19, 1943 the FSSF joined the Fifth Army’s push up Italy. The Force joined Operation Raincoat with the objective being to break through the “Winter Line”. The Allied advance had stalled. The Germans were well dug in. The twin peaks of Monte La Difensa & La Remetenea and surrounding hills formed part of the German defensive position. The Germans had successfully repelled the Allied advance for over a month. Over 20,000 Allied soldiers had tried to break through but to no avail. That was until the Force arrived on the scene.

Following a daring plan, men of the 2nd Regiment would scale the sheer cliffs on the north side of La Difensa and attack the Germans from behind. In very heavy fighting the 2nd Regiment took the crest in two hours. December 2, 1943 the 1st Regiment left for the base of La Difensa one hour behind the 2nd Regiment. The 1st Regiment had been instructed to move south of Hill 368 and assume a defensive position.

The remainder of the month of December 1943 was very busy with taking numerous well defended Hills. The battles mentioned here were mainly the ones that the 1st Regiment, 1st Battalion (S/Sgt Morin’s Unit) were involved in. December 4, 1943 1st Regiment was ordered to start out for Hill 960 (one Hill below Hill 907 – La Remetenea). Almost immediately they encountered a German sniper firing tracer rounds, a second sniper from a different angle also opened fire. A German artillery observer, on another hill, ordered the bombardment of the area where the tracers intersected. What followed was pure hell for the entire 1st Regiment. Artillery shells literally rained in for the next twenty minutes.

High explosives, air bursts, dead-head armour piercing shells, white phosphorous shells, every type of round in the German stockpile fell on the 1st Regiment. There was no moving or getting away from the booming, flaring concentration although a small group of 15 Forcemen did get away to deal with the snipers. In spite of this barrage there remained among the Forcemen a quiet orderliness. Several aid men were hit early; others picked up their kits and went to work on the wounded. The rain made the steep rock paths extremely slippery and throughout there was no alternative, no defence, but to await the finish. Abruptly the shelling ceased and then shifted to another point down the trail. Without knowing it, the enemy had rendered 1st Regiment, which had yet to strike a blow, exactly 40% ineffective. One source states: “on December 4, 1943 based on the incompetence of a Divisional Commander, the 1st Regiment had been badly mauled”.

On December 5, 1943, in spite of the losses, 1st Battalion reformed, closed ranks and moved on up Hill 960 as ordered, 2nd Battalion remained behind to clear the dead and wounded from the battle zone. December 6, 1943 1st Battalion, 1st Regiment overran Hill 960 and continued on the same day to seize Hill 907 (La Remetanea) relieving the 2nd Regiment who had just cleared La Difensa and moved on down Hill 907. December 7 and 8, 1943 were spent dealing with German counter attacks and clearing enemy sniper and mortar nests. December 9, 1943 the 1st Regiment along with the 2nd and 3rd Regiments were relieved on the Line for an 11-day rest period at their Base in Santa Maria.

The Force received many accolades, for the amazing feats they had accomplished, from Major Generals and down. The Force had done their job but the break-through didn’t happen. The U.S. Army was once again bogged down against dug-in German troops occupying “the mountain tops of Lungo, Sammucro and Hill 720”. Several attempts had been made, by seasoned, battle hardened troops to clear the ridges but they had been beat back. Once again the Force was called upon to “clear the high ground”. Throwing the enemy off Sammucro and Hill 720 became the priority.

December 23, 1943 the 1st Regiment departed uphill in the daylight. The hills were hung in clouds almost to their bases, the air was cold and cheerless. Dampness pervaded everywhere. The 1st Regiment was preparing for an assault of Hill 720. As with La Difensa, all supplies had to come up on the backs of Forcemen – 1 pack – 100 pounds at a time. The pack mules couldn’t go where the Forcemen could go.

December 25, 1943. After another brief delay the Allied artillery barrage started at 2 a.m. Almost immediately the Germans unleashed shelling that began to fall on the slopes of Sammucro where the 2nd

Battalion of the 1st Regiment lay shivering from the cold and waiting for the attack to begin. Colonel Marshall of 1st Battalion rushed to the area and assumed leadership of the Battalion and the assault, which got underway just as dawn was about to break. The Forcemen killed the Germans in their makeshift bunkers with well-pitched grenades and covering fire. By 7 a.m. the battle was over. Christmas had been eventful for the 1st Regiment, they had conquered another two Hills. At this point, 1st Battalion quickly closed up to solidify the gain. On Christmas night, except for patrols, 1st Regiment came down from the Hill, bearing its dead, into San Pietro Infine.

The Forcemen, as it was becoming their habit, attacked after dark. The Force had the advantage of these silent, cunning night-time approaches, utterly surprising the Germans, as they lay shivering at their posts. December 26, 1943. That evening a nine-man patrol from 1st Regiment crept up and eliminated a series of machine gun nests on another summit within range of Radicosa; Hill 675. The men virtually crawled into the gun pits with the Germans before giving the command to surrender.

January 1, 1944 a plan was in place to attack and capture the peaks commanding Vischiataro. 1st Regiment was to move to the notch at Forcella Del Moscoso (Hill 708) and protect the flank of the 3rd Regiment. January 2 and 3, 1944 fighting raged through the hills surrounding Radicosa. January 4, 1944, by noon the 1st Regiment had Radicosa and were busy de-fusing the mines and demolition charges set up on the trails and in houses. January 5 and 6, 1944 1st Regiment had poor going in its assault toward Hill 1109 (Mt. Vischiataro). For six hours of slow, painful going, the Assault Companies worked forward to the first rise below Hill 1109, in the process, eliminating many German positions. But in the end, as the enemy defence in depth defied the full remaining strength of the 1st Regiment, and slowly but surely whittled down that strength to a skeleton, it became necessary, in the breaking dawn, to withdraw back to Stefano and reorganize.

From January 7, to January 10, 1944 the 1st Regiment, 1st Battalion fought on in the mountains of Italy in the same manner against German forces. They took Mt. Majo, Hill 1270, Hill 1109 and then Hill 1270 again. January 10, 1944 saw the end of the battles over the Winter Line. They all moved back to their Base at Santa Maria for a well deserved rest. During the mountain campaign the FSSF suffered 77% casualties: 511 total, 91 dead, 9 missing, 313 wounded with 116 exhaustion cases. On January 10, 1944 S/Sgt Morin was awarded the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal (CVSM) and Clasp in the Field with the 1st Canadian Special Service Battalion. When the 1st Regiment first went into battle on December 2, 1943 they had a combat strength of 32 officers and 385 enlisted men. At the end of the action on January 10, 1944, 1st Regiment was down to 7 officers and 82 enlisted men. S/Sgt Morin was one of the 82. For the Force, it had been a cold and wearing struggle in the mountains. Of the Forces 1,800 combat strength on December 2, 1943, approximately 1,400 were either dead, wounded or hospitalized. It is reported that for every Forceman killed they killed twenty-five Germans, for every Forceman captured they captured 235 Germans!

On January 22, 1944 the Allies landed on Anzio Beach and seized a 52-kilometre crescent of the Italian countryside. Very quickly the Germans were able to surround the Beachhead. Pressing on the perimeter were four German Divisions with others arriving almost daily. With the German artillery occupying the high ground (88 mm and 170 mm guns plus two 280 mm railway guns) the Beachhead was constantly exposed to enemy barrages. The two monstrous 280 mm railway guns would eventually be christened “Anzio Annie” and “Anzio Express” by the troops on the beach. Add to this the regular strafing and bombing runs by the Luffwaffe, Anzio Beach, especially during the day-time, was a killing zone.

February 2, 1944 at 10 a.m. the Force was given permission to dock and unload at Anzio Beach, it would be the Anzio Beachhead that would make the Force “a legend”. For the Forcemen the Anzio Beachhead was a complete reversal of their previous combat experience. Flat country instead of mountains and hilltops; defensive positions instead of assaulting dug in Germans. In front of the Force was the Mussolini Canal and German troops. The Force was assigned 13 kilometres of the 52-kilometre Front Line, or one-quarter of the Beachhead. At this juncture, through reinforcements, the Force combat strength stood at 68 officers and 1,165 enlisted men. The remaining 39-kilometre Front Line was assigned to 36,000 Allied soldiers which became close to 100,000 by the day of the breakout.

Initially after the Anzio landing occurred the Germans saw it as a heaven sent opportunity to snatch victory and destruction of an Allied amphibious force. On two occasions, Hitler publically ordered General Kesselring, “to push the Allies on Anzio back into the sea”. What the Anzio landing did achieve was that both sides tied up a lot of troops in a somewhat static four-month standoff.

After first securing its position on the Line, the first night up, the 1st Regiment pushed three Platoon Patrols deep into the enemy front. Probing patrols continued for a week pushing the enemy out of one outpost after another. This pattern of aggressive night patrols would continue for the next three months. Depending on the assignment, these patrols could be Company, Platoon or Section strength and in some cases one or two Forcemen would go out by themselves. The prelude to these Patrols was the blackening of their faces with black shoe polish (S/Sgt Morin would use the residue from burnt wine bottle corks).

February 15, 1944 after a fire-fight between the Force and elements of the Hermann Goering Division, a Commander had been killed and a diary had been found on his body. This officer had made an entry on February 11, 1944 which stated: report from Sessuno of “schartzer teufel” (Black Devils) raid last night. On February 13, 1944 he made another entry which stated: there were many sharp attacks on Vesuv last night and he finished with; “we never hear the Devils when they come, they are all around us”.

The Force now had a nickname; “The Black Devils” [they were also called: The Devil’s Brigade; The Black Devil’s Brigade and Freddie’s Fighters (after Lieutenant Colonel Robert Frederick who built the FSSF). The 1st Regiment nightly Combat Patrols were aggressively pursued in a bid to put the fear of the Force in the Germans. The concept of these Patrols was to move quietly in behind enemy outposts and then strike ruthlessly, eliminating soldiers and their weapons. When circumstances allowed, the Force brought back their own dead, which ratcheted up the terror and mystic of the Force. The enemy would find German dead in the aftermath of a raid but rarely Forcemen.

On one Night Patrol, Lieutenant Gus Heilman, Headquarters,1st Battalion, 1st Regiment lead a patrol of 32 Forcemen across Bridge 1 below the Village of Borgo Sabotino. After an intense fire-fight the Germans, at a canal lock-house, high-tailed it out of there! The Patrol on its return took a shine to Sabotino and duly declared it the new home of the 2nd Company, 1st Regiment. Heilman was declared Mayor and the town renamed Gusville. News of Gusville’s founding spread down the line and boosted morale. Such esprit de corps had to be permitted and Colonel Marshall saw the stunt as an opportunity. He crossed the canal and set up positions on the east bank of the waterway where the 1st Regiment stayed.

February 27 & 28, 1944 frequent attempts to infiltrate the 1st Regiment’s Line were stopped by setting a “trap” and capturing 108 to 111 German prisoners. The attempts were halted.

March was a relatively quiet time for the 1st Regiment. During this period, the 1st Regiment continued their nightly patrols. Forcemen were sent out each night to seize houses for observation. In the day-time the Force outposts pulled back and the Germans would move in. On occasion this tactic would lead to a fire-fight between outpost parties as one moved into the house before the other had cleared out. March 6, 1944 S/Sgt Morin was struck-off-strength to the X-3 List (evacuated on medical grounds) and then on March 7, 1944 he was taken-on-strength with X-3 List 1st Combat Service Support Battalion (1st CSS Bn).

March 10, 1944 the 1st Regiment poked into Cerreto Alto for a second time with a Platoon Raid, showing that a presumed German strong point to be void of defenders. In another area closer to the beach the 1st Regiment noted an enemy observation post on top of the windmill at Cerreto Alto. A package of RS explosives, placed there one evening, toppled the tower. On March 12, 1944 S/Sgt Morin was admitted to 36 US General Hospital and 13 days later on March 25, 1944 he was discharged from that Hospital. On March 26, 1944 S/Sgt Morin was taken-on-strength from X-3 List to the 1st Canadian Special Service Battalion (1st SS Bn), Allied Armies in Italy (AAI).

On April 18th the outpost’s report coming in that night reported heavy enemy road movement in the Piave area that spelled either an attack or strong patrol action against the Force front. This trouble would be dealt with by the 1st Platoon, 1st Company, 1st Regiment, who had advanced astride the road southwest of Borgo Piave and were securing the right flank. As the 3rd Company (S/Sgt Morin’s Unit) started toward the objectives and had moved within 300 yards of Red Road, movement was heard to the right that materialized into three explosions. Three nearby houses had been levelled by German Demolition Patrols. 3rd Company changed directions so the Company would bypass the German demolitions party and get on with the job. Promptly on schedule the Allied artillery came down on the objective at 6 a.m. while the Platoons cut the enemy wire and moved through the gaps, under the covering artillery, close in to the houses. 3rd Platoon moved in on house 8, while 1st Platoon moved on house 5. Shortly the artillery ceased; there was a lull, then eight machine guns opened up from the house line, with a flakwagon (4 – 20 mm guns mounted on the back of a truck) firing from house 9. Both tanks and artillery support were called in to deal with house 5 and 8, the worst nests of resistance, while the Assault Platoons silenced the remaining automatic weapons.

April 24, 1944 the 1st Regiment had the heaviest action with another bombing of Borgo Sabotino (Gusville), with flares and strafing. Later that evening a 1st Regiment Patrol moved to Cerrato Alto, investigating enemy reaction following the raid, they met strong machine gun fire from a farmhouse but managed to pick off ten Italian Marines. April 25th a German swimming party off Fogliano ended in a “naked retreat” when artillery observers in Fitting Out Gunnery (FOG) 3 (one of the 1st Regiment’s coast-watching towers) spotted the swimmers and called for artillery fire on the party.

General Frederick was aware of the usefulness of Psy-ops, early in the Anzio campaign, he had small card-size stickers printed. They bore the Force’s red spearhead emblem complete with national identities USA.- Canada and a personal message to every German soldier along the Beachhead: Das Dicke Ende Kommet Noch, which translates roughly to “The Worst Is Yet To Come”. These flyers proliferated at Anzio. The Forcemen carried them in their cargo pockets, and deposited them on the foreheads of the German corpses or on the bunker thresholds of the living enemy they wanted to unnerve.

May 9, 1944 1st Regiment, along with 3rd Regiment were pulled back off the Line and replaced with other troops. Back from the holes and hollows went the men after ninety-eight days, most of them in the same position, manning the same machine guns, washing every morning in the Mussolini Canal and dining every evening on hard rations and supplemental eggs. Life in those holes had been habit forming and a change was needed: exercise, marches and training in assault tactics.

The breakout from Anzio Beachhead was at hand and the 1st Regiment was given the task of leading the assault. It would be the tip of the spearhead as part of Operation Grasshopper, a drive east to join with Forces in the mountains above Littoria. May 23, 1944 before dawn, men of the First Special Service Force crouched in trenches and waited under a shower of rain as 600 artillery pieces and 60 bombers pounded Cisterna to cut a path for the breakout. The Forcemen knew that once the order to attack was given, 1st Regiment would lead the assault. Despite the rigours of the previous 98 days, 1st Regiment, along with the rest of the Force, was up to the task of leading the assault.

At 6:30 a.m., under the arching mortar fire, the 1st Regiment advanced in a swarming wave. As always, enemy machine guns laid down their immediate lines of fire. Until small groups, Sections and parts of Sections moved in with grenades and automatic fire. The attack took it easy and paused. The rifle grenadiers dropped their “eggs” (grenades) accurately from 300 yards off while Sections moved close in for mop-up, in less than an hour, against reduced machine gun fire, it became easier to advance.

By 10 a.m. advance Sections had cut across Highway 7, isolating Cisterna from the south and Littoria from the north; 20 minutes later 1st Battalion, 1st Regiment was digging in to hold the railroad embankment. First objective had been taken. At noon Allied artillery observers reported a heavy concentration of enemy infantry and armour sheltering in a 10-acre stand of woods. Allied artillery raked this target at maximum capacity for 20 minutes while a flight of dive-bombers added their bombs. Most of the German infantry were annihilated in the woods but the tanks came out. Then the trouble started for 1st and 3rd Companies on the railroad bed, while 2nd Company blocked the Highway.

Due to the failure of the Pollack Force to come abreast at Highway 7 the whole left flank of the 1st Regiment was vulnerable to whatever the enemy had to offer. For 1st and 3rd Companies ammunition was low and resupply difficult. The only road forward came under fire from the open flank. A heavy artillery cross-fire from Cisterna on the left and Littoria on the right beginning at about 12:30 p.m., started to work over the1st Battalion, 1st Regiment on the railroad embankment. It became impossible to move up reinforcements and ammunition while the artillery curtain continued and continue it did. The situation was not improved when enemy tanks opened fire on the 1st Battalion.

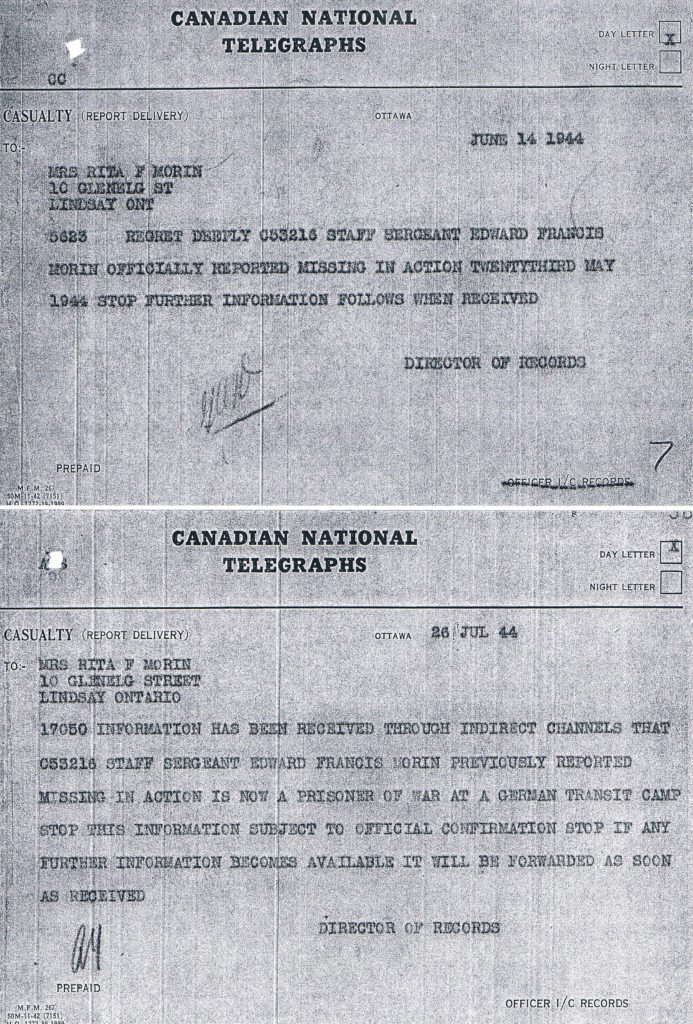

By 3 p.m. the Germans had moved enough armour into the area to hold superiority on the front. The big tanks (Tigers and Mark V Panthers) moved in on 1st and 3rd Companies which were dug in but pinned down along the railroad and the Mussolini Canal. About half of 1st Company got back to the Highway. 3rd Company was badly cut up, with most of the Company missing. It was later learned that on May 23, 1944 17 Forcemen of 3rd Company had been taken prisoner. For S/Sgt Morin the fighting was over. He would now spend the next year in a German prison camp. For a period of time following this engagement S/Sgt Morin’s status was unknown and he was simply listed as missing in action. It would be the Red Cross who would later confirm that he was a Prisoner-of-War. A year later, Forcemen of 3rd Company, would tell their story to old Forcemen while being evacuated from the Prison Camp. They would say that “the Germans walked us for three days and nights steadily, but the boys kept right on going and wore out three sets of guards”.

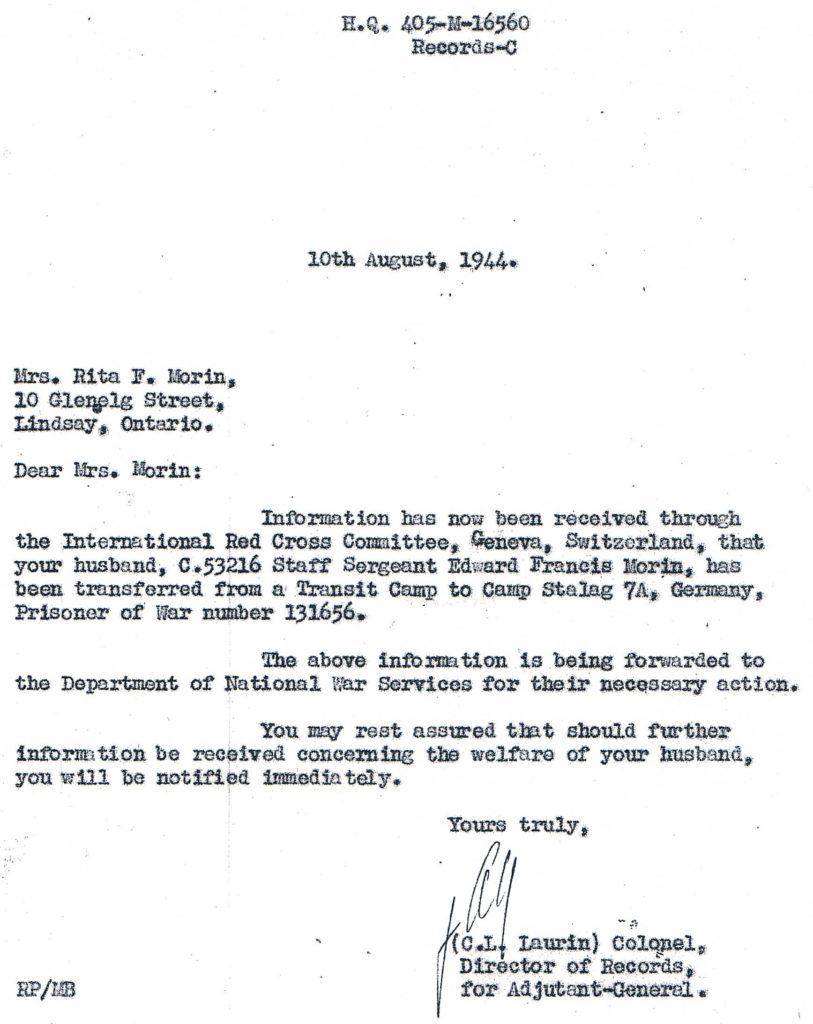

On May 23, 1944 S/Sgt Morin was reported missing and was struck-off-strength from 1st CSS Bn to the X-1 List (Prisoner-of-War – verified). May 24, 1944 he was struck-off-strength from the X-1 List to the X-6 List (posted as missing). It was then stated that the previous report of missing was now reported as being a Prisoner-of-War (POW) of the German POW No 2, Transit Camp, Germany. [Recent information had revealed that S/Sgt Morin was held in Stalag 7A Mooseburg, Bavaria and was liberated on April 28, 1945 by the American Combat Command A, 14th Armoured Division.] August 31, 1944 S/Sgt Morin was struck-off-strength from the X-6 List and was taken-on-strength to the Canadian Army (Overseas) CMF with 1st CSS Bn, AAI. He was then taken-on-strength by the Canadian Armoured Brigade (CAB), Central Mediterranean Force (CMF) while remaining on strength of 1st CSS Bn.

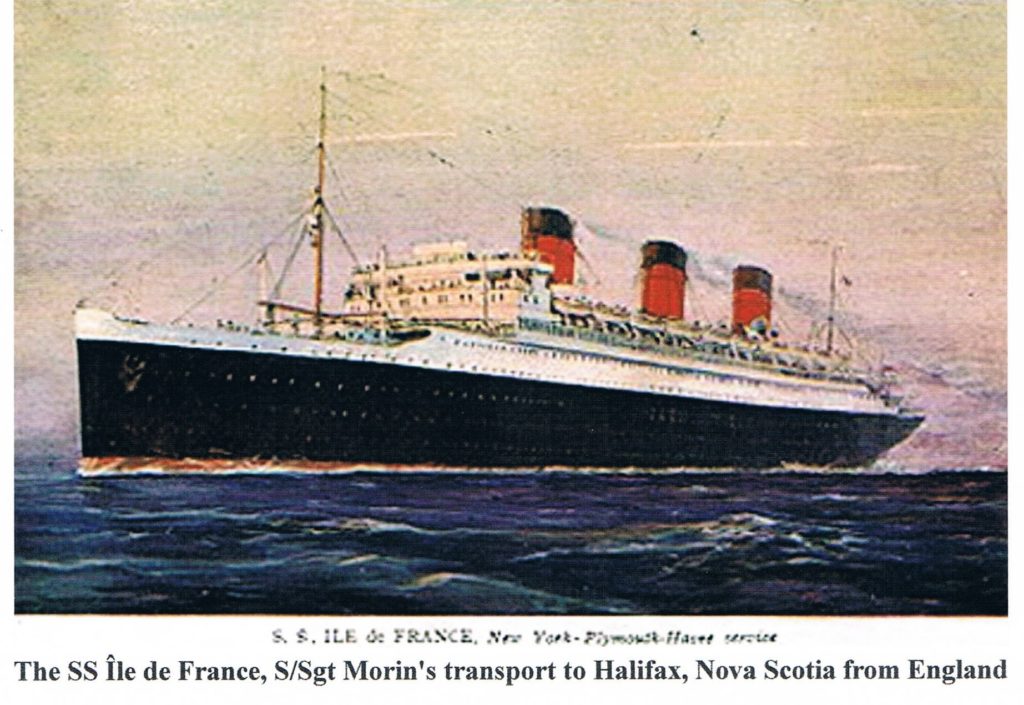

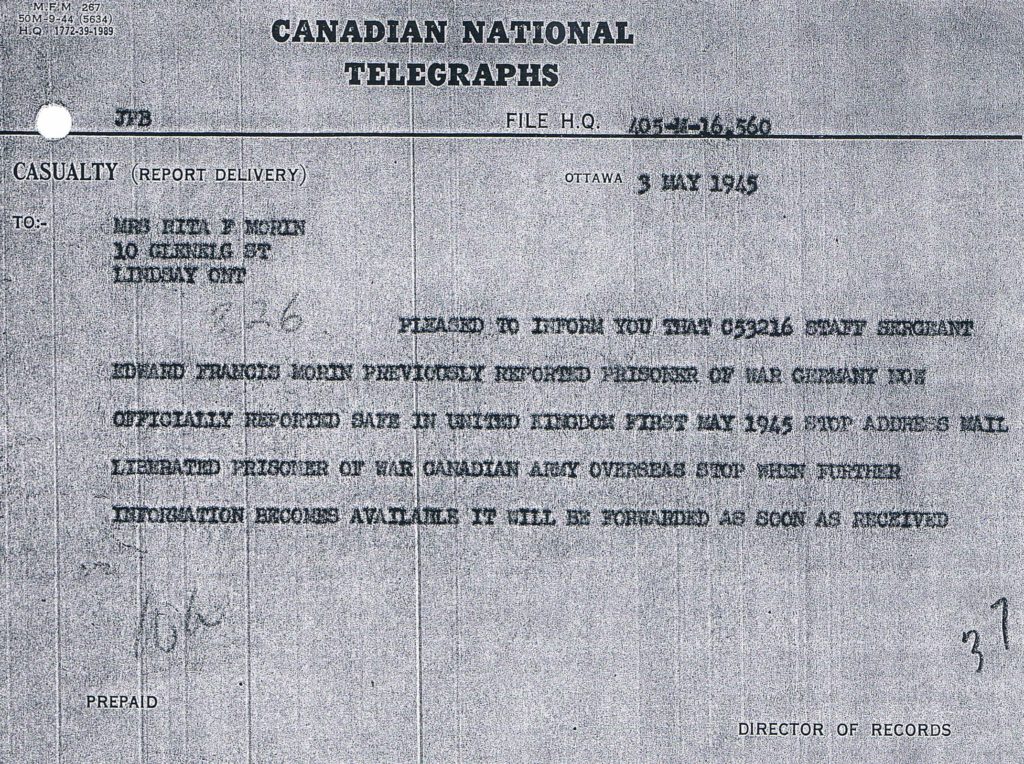

On May 1, 1945 S/Sgt Morin is now safe in the UK! He had been a POW for 11 months and 1 week. On his release his weight had dropped to 98 pounds. Privileged report, with No 1 Canadian Reception Depot (No 1 CRD), from the POW List 102 and admitted to No 4 Canadian General Hospital (CGH), May 1, 1945. On discharge from the No 4 CGH on May 5, 1945, he is with No 1 CRD again. June 13, 1945 S/Sgt Morin is struck-off-strength from the Canadian Army (O/S) and No 1 NETD to the No 1 CRD in the UK. On June 15, 1945 he is taken-on-strength to No 9 DD (Echelon), Ottawa, Ontario from the Canadian Army (Overseas). Although not entered in his Records, S/Sgt Morin probably embarked England June 12, 1945 aboard the SS Île de France to arrive in Canada about June 23, 1945. He returned on the same ship as Allan and Arnold Graham; they had known each other well when growing-up in the Village of Lakefield.

On June 23, 1945 S/Sgt Morin was granted 35 days disembarkation leave and Rations Allowance to July 27 1945. July 20, 1945 he was struck-off-strength to X-9 List (personnel held at Base Reinforcement Units, disposition to be decided), Canadian Infantry Corps (CIC), No 9 DD from X-9 List DD. On July 21, 1945 S/Sgt Morin was taken-on-strength to X-9 List CIC, No 2 Echelon. On July 31, 1945 he ceased to draw Parachutist pay. On August 1, 1945 he was granted a 7-day extension of leave plus 2 days travel time. On August 16, 1945 S/Sgt Morin was removed from the X-9 List (No 9 DD) and placed on the X-12 List (at Depot awaiting discharge) No 9 DD and then taken on strength to X-12 List (No 9 DD) August 17, 1945. On August 22, 1945 S/Sgt Morin transferred to No 9 DD (Holding Establishment) from X-12 List No 9 DD. August 23, 1945 he was taken on strength with 1st CSS Bn, No 9 DD (Holding Establishment).

On August 24,* 1945 S/Sgt Morin was struck off strength from the Canadian Army on discharge, according to his File; on demobilization. He was granted a Clothing Allowance of $100.00 and a Rehabilitation Grant. On discharge S/Sgt Morin lived at 622 Park St., Peterborough Ontario.

* S/Sgt Morin’s Discharge Certificate has August 21, 1945 as the official date of discharge.

Staff Sergeant Edward Francis Morin served: in Canada for about 1 year, 6 months and 18 days; 9 months and 12 days in England; 1 month in the Aleutian Islands – Alaska; 1 year, 3 weeks in the USA, 8 days in North Africa and 1 year, 5 months and 14 days in Italy and as a POW. His total service, including travel time, was 5 years, 1 month and 3 weeks. He earned the following medals and awards:

1939 – 45 Star, Italy Star;

Defence Medal;

Canadian Volunteer Medal & Clasp; and

War Medal 1939 – 45.

He would have qualified for the General Service Badge Class A.

The Regiment formally termed “The First Special Services Forces” has been the subject of several books, with a movie made of their exploits, starring William Holden. It was the first fighting force of that style. However, since then, most nations have recognized the benefit, of organizing and training similar groups. The US Navy Seals, successfully involved in the delivering of justice to Osama Bin Laden, has many similarities of the Regiment.

During 251 days, in combat missions the Force incurred 2,314 casualties or 134% of the authorized combat strength of 1,800. During combat American casualties were replaced on a regular basis, but from a Canadian perspective, there was only one influx of Canadian reinforcements in April 1944, just prior to the breakout form Anzio.

As already stated, it is reported that: for every Forceman killed they killed 25 of the enemy, for every Forcemen captured they captured 235.

An excerpt from an article in McLean’s magazine by Barbara Amiel, September 1996:

The military is the single calling in the world with job specifications that include a commitment to die for your nation. What could be more honorable?

What follows are a few comments, by individuals who knew the men who served in the First Special Service Force:

”When you talked to them, you had no idea whether you were speaking to a Canadian or an American, they were Forcemen. They are soft in speech, gentle in manner, but fierce in battle”.

”The men of the Force never took a backward step in battle. They prized, beyond the fear of death, the dignity which came from belonging to the Devil’s Brigade. They are warriors”.

”The men of the First Special Service Force are the best God damned fighters in the world”.

It was said of the First Special Service Force: ”Few Units, in World War II, equaled the glowing reputation established by the First Special Service Force. It never met defeat in battle. It accomplished the most difficult of missions with an eagerness and proficiency that astonished outside observers, including the German’s. In size, the Force was equal to an Infantry Regiment, and yet the Force consistently accepted tasks more appropriate to a regular Division. Moreover, the Force remained effective even after it had sustained causalities that would have incapacitated another unit”.

During 251 days, in combat, the Force suffered 2,314 causalities, or 134%, of its authorized strength of 1,800. It is reported that: for every Forceman killed they killed 25 of the enemy, for every Forcemen captured they captured 235.

It was based on their success in combat and their reputation as an elite fighting force, that ”the 114th Congress of the United States of America, on February 3, 2015, granted the Congressional Gold Medal, collectively, to the First Special Service Force, in recognition of its superior service during World War II”. It was said during the presentation: ”The United States is forever indebted to the acts of bravery and selflessness of the troops of the Force, who risked their lives for the cause of freedom”.

July 27, 1944

Previously Missing, is Now War Prisoner

__________________________

Mrs. F. Morin, 10 Glenelg St. E., (Lindsay) received word today that her husband, S-Sgt. Edward Morin, previously reported missing since May 23, 1944, is now reported to be a prisoner-of-war in Germany. S-Sgt. Morin is serving with the “International Paratroopers”, attached to the Fifth American Army in Italy.

1944

Mail ends silence of two months

Mrs. E.F. Morin of Lindsay, Ont., received word from her husband, who is a Prisoner-of-War in Germany, today for the first time in nearly two months. The letters were dated the 1st of Oct. and Nov. 5. In his first letter he stated that the Germans had just brought in some new prisoners and he was talking to one of them. S/Sgt. Morin said that the soldier with whom he was speaking, was from Lindsay and that his name was King. He also stated that he met some other fellows from around this district.

In the letter dated November 5, he stated, “I have received 5 letters from you today, and was very happy to hear that Eddie Jr. and you were doing fine. Things haven’t been going so well around here for the past two weeks, as we have not received any Red Cross parcels and no cigarettes.”

S\Sgt. Morin was taken prisoner in Italy on May 23rd at the Anzio Beachhead, while serving with the First Special Service Force, a combination of United States and Canadian Paratroopers.

1945

Husband is freed from prison camp

S\Sgt. Morin released from Stalag VII A Mooseburg, Bavaria

Mrs. Rita Frances Morin, of 10 Glenelg St. E., has just received word that her husband, S\Sgt.

Edward Francis Morin, has been released from Stalag VII A Mooseburg, Bavaria, and has been in

England since May 1st.

S\Sgt. Morin joined the Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry Highlander in Peterborough in July, 1940. He went overseas early in 1941. S\Sgt. Morin returned home to Canada as an instructor in the King’s Own Royal Rifles of Canada and trained men in Moose Jaw, Sask,, and also in Terrace, British Columbia.

He volunteered as a paratrooper for the First Special Service Force, a combination of Canadian and American troops and trained at Helena; Montana, Burlington, Vermont, and also in Norfolk, Virginia. He was in the raid on the Aleutians and returned home for a short leave before going to Italy. S\Sgt. Morin was in Italy when taken prisoner on the 23rd day of May, 1944.

The Post joins with the community in wishes for an early welcome home for S\Sgt. Morin.

June 20, 1945

Ex-Prisoner Of Germans Nears Home

__________________________

Staff–Sgt. E. F. Morin, whose wife and family resides in Peterboro, is reported to have arrived in Halifax this A.M. Sgt. Morin was a prisoner of the Germans for eleven and a half months, and his arrival in the Dominion puts an end to his long anxious months away from home.

He is expected in Lindsay where it has been arranged he will meet his wife at an early date.

PERSONAL HISTORY

EDWARD FRANCIS MORIN

Edward Francis was born March 15, 1919 in Peterborough Ontario and was raised in Lakefield on Dean St. at the corner of Concession. Edward Francis went by the nickname “Eddie”. His mother had died when Eddie was 1 year, 7 months old and he was raised by his aunt Emily, Mrs. Fred ‘Brigham’ Young and her husband. His older brother Wilfred, who was always called “Woody” went to live with another aunt (their father’s sister) who lived in Cobourg. However after 10 years Woody also came to live with Aunt Emily. Their father, Joe Morin, brother to Emily Young, also lived in the household, as did the Young’s two daughters, Pearl, who by marriage became Mrs. Darcy Wilson, and Frances, who married George Jessup. Such was the love, atmosphere and acceptance of one another in the Young home that Eddie and Woody were known, and totally accepted as brothers to Pearl and Frances. Brother Woody also enlisted with distinguished service in the Canadian Navy during World War 2.

Eddie attended school from 6 to 15 years of age; he played baseball at the short-stop position and soccer as a forward. He also enjoyed hunting, fishing and ice skating. He completed grade 8 and then went out to work. In the period of 1934 to 1936 he worked at the Peterborough Canoe Company as a boat-builder’s helper for 18 months. His pay was $12.00 per week. In the period of 1936 to 1940 he worked as a boat builder with the Peterborough Canoe Company, a labourer and doing odd jobs. He displayed good skills in his tasks and earned $18.00 per week. Eddie worked for 6 months piling lumber in Lakefield for Fred Lawrence. He was skilled in driving automobiles and a power launch.

Edward Francis married Rita Frances Kelbrick, born March 2, 1919 in Lindsay Ontario, on January 7, 1941 in Peterborough.

When the World War II began Eddie volunteered for Army service and joined the Stormont Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders. They had a recruitment centre in the Peterborough Armories and Lakefield boys Jack Mose, Bill McFadden, Fred Marsden, Gordon “Jiggs” Hill, and his brother Sherman Hill all joined the same Regiment, The “Glens” (Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders).

After returning home from the War, Eddie, and his wife Rita, lived at 622 Park St., Peterborough Ontario. The Peterborough Canoe Company had promised him a job after his discharge, however, he desired mechanics related employment. Eddie had indicated a desire to have a job in an industrial plant such as the Quaker Oats Company. Since he worked in the Outboard Marine he obviously got the employment he desired. Eddie & Rita had two sons Edward John Joseph (Ted), born in Lindsay Ontario and Joseph Robert (Joe) was born September 16, 1946 in Peterborough. Edward John Joseph married Mary Anne Francis Crook (born in Toronto) in Peterborough. They have two daughters, Kristina and Kathleen both born in Peterborough and both are married.

Eddie also told Veteran’s Affairs that he planned to use gratuities and credits to establish a summer resort in the vicinity of Peterborough as a side line. It was stated that he requires insurance under the Veteran’s Insurance Act and a small holding under the Veteran’s Land Act.

Many would argue that it is somewhat improper to class any one soldier to be more important than another. Perhaps that may be so in the overall totality of the role. Yet, how would one relate the importance of someone who just saved their life, or combined in actions which are known to have saved thousands of lives?

Eddie and his fellow soldiers became experts in weapons, hand to hand combat, parachuting, rock climbing, skiing, explosives and demolition. Attaining the maximum physical condition and endurance, they were conditioned to persevere in severe weather conditions, and to maintain control in stressful situations. They became the very best in the world at guerilla, commando style warfare.

Eddie’s proficiency, temperament and leadership ability led him to being promoted to Staff Sergeant. The rank indicated that he was second in command, to an officer, in leading a platoon of 24 men, and would be charged with the responsibility of putting officer’s orders into action. This promotion indicated the faith, respect and confidence which superiors and fellow soldiers placed in Eddie’s competence to best adapt tactics, attain goals, and react quickly to life threatening situations. Indeed, Eddie had proven himself to be one of Canada’s “elite”.

He was “One Hell of a Soldier” was the layman’s description most often offered regarding Lakefield’s Eddie Morin. Eddie, never called Edward, nor even Ed, by those who knew him, received more respect and acclaim from his peers, than any other Lakefield soldier. The admiration and description of fellow Lakefield friends and veterans proclaimed Eddie to be the ultimate soldier. He was known around the Village as being extremely modest, quiet and reserved, while possessing an intense inner confidence. In the many years since WW II, his name was often mentioned. Eddie was always spoken of with reverence by those, who knew him, and especially among those knowing veterans who had also experienced the demands of battle.

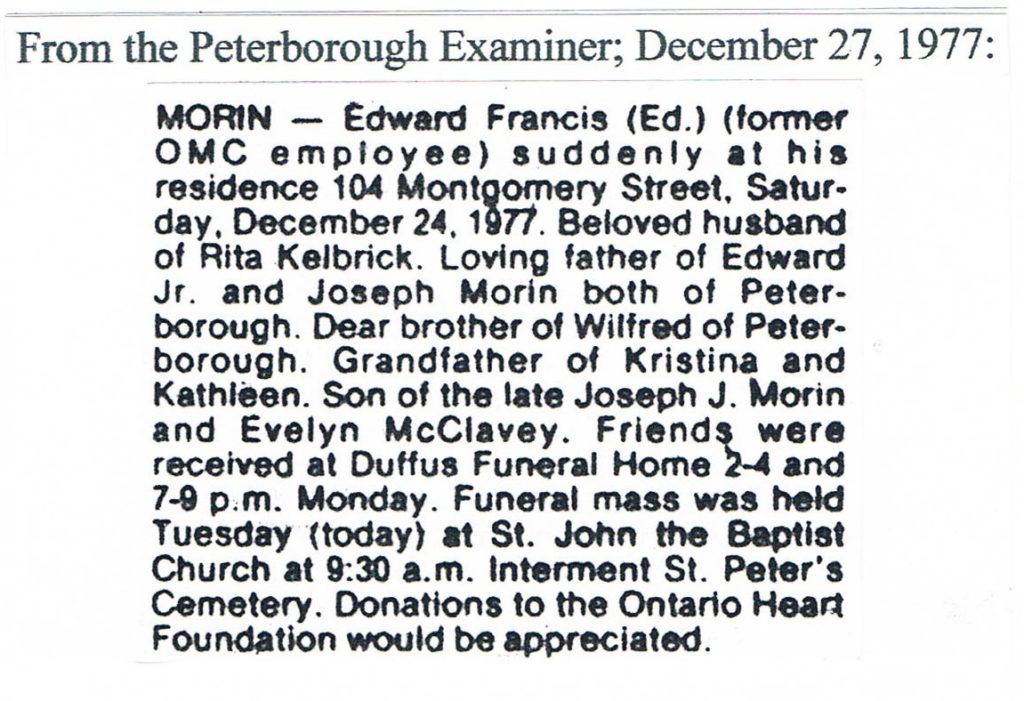

In the early 1970s Eddie was diagnosed with blocked arteries; this necessitated triple by-pass surgery which was done. Edward Francis Morin passed away December 24, 1977 at home, 104 Montgomery Street, Peterborough Ontario. Eddie and his wife Rita are interred in St. Peter’s Cemetery, Peterborough Ontario. Eddie’s son, Ted, states that his dad was a warm, quiet, soft spoken, gentle parent and has had some difficulty reconciling his father with the nature and role of this fighting Force. Indeed he was, as described by his Lakefield buddies: “One Hell of a Soldier”.

MORIN – Edward Francis (Ed.) (former OMC employee) suddenly at his residence 104 Montgomery Street, Saturday, December 24, 1977. Beloved husband of Rita Kelbrick. Loving father of Edward Jr. and Joseph Morin both of Peterborough. Dear brother of Wilfred of Peterborough. Grandfather of Kristina and Kathleen. Son of the late Joseph J. Morin and Evelyn McClavey. Friends were received at Duffus Funeral Home 2-4 and 7-9 p.m. Monday. Funeral mass was held Tuesday (today) at St. John the Baptist Church at 9:30 a.m. Interment St. Peter’s Cemetery. Donations to the Ontario Heart Foundation would be appreciated.

THE EDWARD FRANCIS MORIN FAMILY OF LAKEFIELD

Francois Morin, Edward Francis’s grandfather, was born September 15, 1841 in the Village of Gaspé, Québec. He married Philoméne Mallon about 1868, probably in Québec and they had at least nine children; six sons and three daughters. The first seven children were born in the Village of Gaspé, Québec and then the family moved to Lakefield, Ontario about 1885. The last two children were born in Lakefield. One of the sons, Joseph Jeremiah, became Edward Francis’s father. Joseph Jeremiah married Catherine Eveline McClavey (she went by Evelyn) on November 27, 1913 at St. Peter’s Cathedral of Peterborough, Ontario. They had two sons, both born in Peterborough; Wilfrid, born April 11, 1916 and Edward Francis, born March 15, 1919.

Edward Francis’s parents, Joseph Jeremiah Morin born January 19, 1888 and Evelyn McClavey born Catherine Eveline August 9, 1883, were married in about, 1915. Joseph “Joe” Jeremiah Morin was a boat-builder and lived in Lakefield Ontario; he died December 21, 1943. Evelyn Morin died in Peterborough October 16, 1920 due to having Pulmonary Tuberculosis for 4 months. They had two sons born of French Canadian/British heritage; Wilfrid Morin born April 11, 1916 in Peterborough and Edward Francis was born March 15, 1919 in Peterborough, Ontario.

The Devil’s Brigade: Not Much Publicity Until Now Saturday, February 17, 1968

By GEORGE BURRETT

Examiner Staff Reporter

Twenty-four years ago this week, what was left of the First Special Service Force was digging in on the right flank of the Anzio beachhead on the west coast of Italy. It had come through some of the fiercest fighting of the Italian campaign that winter, splitting the German winter defence line in mountain-top, toe-to-toe battles that opened the way for a stalled Fifth Army group.

Scattered through the Force’s three regiments were men who enlisted in the Peterborough area. They don’t talk much about those days. “It was a long time ago,” is the first reaction when asked to recall some of it.

In fact the Devil’s Brigade never has received much publicity, and the film makers are only now getting around to making a movie on their exploits which is due to make its world premiere in Windsor and Detroit, May 15. It stars William Holden

It will open in the American and Canadian cities simultaneously, because the Force was a mixture of Americans and Canadians. And its survivors say the fusion of fighting men from two countries worked out just fine. Many still hunt and fish together, and. there is that yearly get-together somewhere in North America.

THE HUMAN S1DE

Their greatest fear right now is what Hollywood has done to “the Force”. Their fear is justified, they say, because a quick glance at the book “The Devil’s Brigade”, on which the movie was based, suggests those grenades might be blowing up whole buildings and tanks and things in yet another movie. And it really wasn’t that way.

But then a lot of the human side of the book is just about right — like that day the trainload of wine pulled to a stop beside the train carrying the Brigade. And they had a huge drunk.

“We always did get away with more than other groups,” recalls Mel Parnell, who was with the Force from its formation and training days in Helena, Montana.

Ted Johnson, Ed Morin, Ron Summers, Ed Crowe and Tony Schiarizza are other

Peterborough men who went to the Force. There was also Glenn Crowe and G. H. Junkin of Bobcaygeon, Fred Hill of Havelock, “Curly” Crew of Campbellford, and Bus Morley, now in England.

There are others. Many more were injured in training and never went over with the Brigade.

Others, like Emmett Guerin of Peterborough. G. B. Gardner of Lindsay and H. K. Richardson of Warkworth didn’t make it back.

Some of the men went to Toronto a week ago to speak to their former commanding officer, retired U.S. army Maj.- Gen. R. T. Frederick, brought north by the movie studio as part of the film promotion. Others may be invited to attend the premiere showing in Windsor May 14. Others will wait until it comes this way.

Formed in strict secrecy and deployed quietly to the trouble spots in 1943 and 1944, the Devil’s Brigade did not get much wartime publicity, of necessity. And in December, 1944, it was disbanded because of the lack of properly trained troops to fill its depleted ranks.

FEW TRUCKS NEEDED

After the battles in the mountains — Difensa, Remetanea, Majo and Sammucro and Vischiatara, few remained in shape for the battle at Anzio that was soon to come.

The book notes few trucks were needed to bring the Force back to its bivouac area from the front on the afternoon of Jan. 17, 1944.

“Of its 1,800 combat personnel, 1,400 were either dead or in hospital as casualties. The service battalion packers and litter men were reduced 50 percent by fatigue and wounds.”

Ted Johnson plans on making it to the yearly reunion in mid-August. This year it’s in Pittsburgh, Penn.

The Hotel managers don’t put away the glassware for these reunions any more. Not like in the early post-war years when “Freddy’s Freighters” got together. “They have not torn places apart for quite a while.”

Ted is Secretary – treasurer of Godson Motors (1967) Ltd., married, and has three children. He had to overcome the physical handicap of shattered legs after a direct mortar hit in the battle for Monte Majo.

He attended school in Peterborough, and was in the Prince of Wales Militia before the War. When it went active, he was a sergeant. The summer of 1942 saw him in Helena, Mont., a member of the First Special Service Battalion. “They made it sound quite attractive,” he recalls. “Of course, nobody thought it was going to be a soft touch. He made his first parachute jump on the afternoon of the day he arrived at camp.

They trained in the field in the daytime and went to lectures at night. That winter they learned to ski, taught by professional skiers from within their ranks and Norwegians brought to the U.S. for that purpose.

DRILL FORM

There was not much work on the parade square. “I think they would have been a disgrace to any army as far as drill field form was concerned. Just as long as you could march.”

They marched, skied, jumped, climbed mountains, and were trained in the handling of every make of automatic weapon and explosives. Later they were to prove they could move faster in action than the other allied groups, and were always out front.

But being out front held its dangers too. When Ted was hit, only 80 men out of 600 were left active in the third regiment.

Morale was high throughout “higher than in any outfit I have seen,” he recalls. Those yearly get-togethers now reflect it, a quarter of a century later.

Mel Parnell was in the same company (sixth), as a staff sergeant. He got to see Anzio and Gusville, the little Italian village they named after one of their officers. They stocked it with wine and farm animals from the area. It was out front on their lines, far from the main defence position on the Mussolini Canal.

His platoon kept a goose, which supplied the men with an egg every day. “And there were all kinds of cows roaming around when you wanted a slice of beef,” until word came down to leave the livestock be.

Like the others, he is “afraid of what this motion picture is going to be”. But if there is something about Gusville, as taken from the book, “that is pretty accurate”.

That wine sequence on the trip by rail from Casablanca to Oran was also very real. A train carrying wine in casks parked right beside their coaches, was just too much to resist. Many later sipped it from their helmets.

The train traveled 300 miles on the last leg of the trip from Kiska in the Aleutian Islands to Italy, where the Brigade was blooded.

“We were supposed to be a fast moving outfit,” Mel recalls. “But we had a lot of fun too.”

He was in his late 20s, and the Parnells had two children when he signed up. It wasn’t for adventure; “‘I would hate to see my own young lad go into the army.” “But I knew they needed men; so I, went.”

NO RECOLLECTION

According to the book on the Devil’s Brigade, many of the men from the U.S. Forces that joined it came out of army stockades. And a Canadian in the outfit, a safe cracker, returned to his trade after the War and became known to the Toronto police as the “polka dot” gang. He was apparently a “gang” of one, and he blew himself up with a bottle of nitroglycerine rather than be taken by police when he was finally cornered.

But the Peterborough members of the Brigade do not recall the criminal types. If they were there, it didn’t matter anyway. There were men from just about every fighting unit in Canada and the U.S. in the Force. Morale could not have been higher.

Ed Morin believes the mixture of men in that outfit — I don’t think there was a unit in Canada that was not represented” — and first class officers made it a good one to be with.

A member of the Glengarry Highlanders, he came back to Canada from England in 1942. That summer he became a member of the 3rd Company, 1st Regiment of the SSF, a staff-sergeant like the others.

Being a staff-sergeant helped equalize the pay differences in the ranks — but it still paid $2.50 less a month than the $100 American private. “We were better crap players than they were though,” Ed remembers. More equality.

Their officers were tops. In his experience, “lawyers and school teachers made the best officers . . . school teachers especially”.

Why?

“Maybe they took the best attitude in training their men. Of course many others made good officers.” It is said more men receive field commissions in the Brigade than any other outfits in the War. They were always leading their men in battle.

SKI AS WELL

Ed served under four company commanders who died. One of them, Capt. Ed Bordens who made a 1600-mile, 91-day ski trek from Fairbanks, Alaska, into British Columbia before the War, wanted his men to ski as well as himself.

But that night they scaled Monte Difensa, and Ed recalls him saying “guts go farther than brawn.” He died the next day.

In the breakout from Anzio, Ed was among the spearhead company that was nipped off when the Germans turned, not far from Rome. He spent the next year in prison-of-war camps with 17 of his fellows

Speaking to his former commanding officer, General Frederick, he learned how lucky the Force was when it was not given the assignment it was formed for. “Col. Fredericks thought it would have been a suicide mission, and said so in a report he made to his superiors then.”

Dreamed up by a brilliant, eccentric Englishman by the name of Geoffrey Pyke, the Force became a pet project of vice-Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Winston Churchill and the American chiefs of staff, including Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The plan was simple. They would make a commando attack of brigade strength on the factories, dams and bridges of occupied Norway which were then producing much of Hitler’s war supplies. Equipment and. men were to travel swiftly by snowmobile and skis.

But by the time they were prepared for it, the Norwegian government — in — exile thought less of seeing their homeland blasted.

And military men were having dark, private thoughts about the chances of success.

Their first “action” then was a dry run on Kiska, outermost of the Aleutian chain. The last of the Japanese forces left the island the same night they landed on the other side.

Their only battles up until then had been with the MPs and shore patrols, who almost invariably came out worse for the wear against these men trained in the ways of hand to hand combat.

But in the winter of 1943 – 44 they were to go into some of the fiercest battles of the War.

The Green Berets fly the battle colors of their predecessors with pride.

But Mel Parnell often wonders what it was all about away back there a quarter of a century ago.

“What did we achieve? I don’t think there is any end to it.”