Signaller William George Ogilvie – 344853 – ACTIVE SERVICE (World War I)

On August 23, 1916 William George Ogilvie completed the Attestation Paper for the Canadian Army, Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). He was 18 years, 5 months old when, as a single man, he enlisted for the duration of the War. William George was born in Lakefield, Ontario and gave his birth-date as March 7, 1898. William George indicated: ”he did not presently belong to an Active Militia, but he had served with the 46th Regiment, in Peterborough”. Although there is nothing on his File to indicate where he was educated or to what level it is known that he attended both Elementary and High School in Lakefield, in fact William George was attending Lakefield High School when he enlisted. As far as his Trade or Calling is concerned, he lists Student. William George was 5′ 8½” tall, with a 36” chest (expanded). His weight is not listed. He had a fair complexion with gray eyes and brown hair. His Medical Examination was conducted in Peterborough on August 23, 1916; it indicates that he had no medical issues and was deemed fit for Overseas duty with the CEF. William George’s next-of-kin was listed as his father, George Gilbert Ogilvie, of Lakefield, Ontario. William George Ogilvie signed the Oath and Certificate of Attestation on August 23, 1916. The Certificate of Magistrate was signed by the Justice on August 23, 1916 in Peterborough. On August 23, 1916 William George was taken-on-strength with the 74th Recruiting Battery (RecBty), Canadian Field Artillery (CFA); he was assigned the rank of Gunner (Gnr) and Regimental Number 344853.

Gnr Ogilvie and the 74th RecBty received basic Military Training at Camp Barriefield, Kingston Ontario. While in Camp Barriefield the men lived in Bell tents. Their days were filled with endless drills; marching about with wooden rifles and forming fours. The 74th RecBty then moved to Camp Petawawa, Ontario for Artillery Training. It was here that they were trained in the use of real Artillery pieces (18 Pounders and 4.5” Howitzers). They learned the anatomy of horses, the care and feeding of them, as well as the names of all parts of the harness used for hitching up six-horse gun teams. Based on previous experience with horses, Gnr Oglivie was switched to being a Driver, of horses, either as a six-horse hitch hauling the Artillery guns or Ammunition Trains hauling ammunition. This was followed by a transfer to the Signals Section where he became a Signaller (Sgr). With the Signals Section Sgr Ogilvie learned Semaphore, Morse Code and how to use the Aldis Lamp and Heliograph.

Sgr Ogilvie’s Military File indicates that he embarked from Halifax, Nova Scotia on November 23, 1916 aboard the S.S. Mauretania. Prior to his departure he was granted a Leave back to Lakefield.

November 30, 1916 on disembarkation at Southampton, England Sgr Ogilvie was taken-on-strength with the Reserve Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery at Shorncliffe, Kent County, England. The next several months were spent in intensive training which included, in part, Artillery practices, Rifle Drills, Signals and Horse Handling, including riding.

On June 22, 1917 Sgr Ogilvie was struck-off-strength from the Reserve Brigade and was posted to the 2nd Reserve Artillery.

On July 11, 1917 Sgr Ogilvie was struck-off-strength from the 2nd Reserve Artillery upon being drafted to the 4th Canadian Divisional Ammunition Column (CDAC) and embarked England. On July 12, 1917 he disembarked in France at Boulogne and was attached and posted to the 4th CDAC, as a reinforcement. The Unit now boarded a train for the 20 kilometre trip to Étaples in the rear of the Lens Front-Line. For the trip the men were loaded into Box Cars, known as 40 x 20’s, because they had a capacity of either 40 men or 20 horses. On July 17, 1917 Sgr Ogilvie joined the 4th CDAC, in the Field.

Being attached to an Ammunition Column, using horses and mules, it was their job to transport Artillery pieces and ammunition to the Front-Line. To avoid detection by the enemy these movement were usually carried out at night.

An excerpt from William George Ogilvie’s book, UMTY-IDDY-UMTY – The Story of a Canadian Signaller in the First World War: ”It was August 15th, 1917. The attack on Hill 70 had commenced with a heavy barrage, in the early hours, with the advance of the troops following as soon as it became daylight. It wasn’t long before another Signaller and I were called into Major Phippen’s office. Our orders were to go up towards Hill 70 and follow the advancing troops in search of German telephone equipment. Hill 70 was not directly ahead of our part of the Front and we had to walk two or three kilometres to our left before we could go forward to where the battle had taken place and where our troops were consolidating the ground they had captured. Although it was a hike of at least eight or nine kilometres before we arrived at the first line of trenches. We had never seen trenches before outside of pictures and the maze we were now approaching was completely foreign to us two rookies. Although the gun-fire had greatly abated there were a few shells dropping here and there over the battlefield. We must have been gawking like babes in the wood when we were accosted by a Major who asked us what the hell we were doing up in the Front. We told him our orders and showed our passes. With a brief glimpse he handed them back to us with a muttered curse which spoke volumes of scorn for anyone foolish enough to send a couple of strays while a battle was still being fought. Stretcher parties were emerging from the nearby trenches, carrying out wounded and he ordered us to pick up a stretcher and help. We had no option but to obey orders. Our sortie for telephone equipment was forgotten. Entering the trench for the first time we passed many groups of walking wounded and grey-clad prisoners, some of them occupied as stretcher bearers. Large groups of prisoners passed us under the guard of only one of our soldiers. The fight seemed to have gone out of them and they looked as though they were only too glad to be getting out of the battle zone alive. Further along the trenches we found a wounded soldier and carried him back out to the field dressing station. After a number of trips, it was decided as the afternoon had passed and it would soon be getting dark, the time had come to head back to our post. The battle seemed to be over and we trudged on, weary and bone tired. This had been our first visit to a battle front and the wild scene of devastated area just back of the trench-lines was a grim eye-opener as to what war was really like”.

Shortly after this experience, Sgr Ogilvie came down with what was described as Trench Fever and was taken off duties for two weeks.

Based on his own request to be transferred out of the Ammunition Column and to an Artillery Brigade, on October 3, 1917 Sgr Ogilvie was attached to the 4th Canadian Divisional Artillery (CDA).

After being transferred to the 4th CDA, the Division began a series of moves from the Lens area to Steenvoorde (near the Ypres & Passchendaele Salient, to Ypres Asylum (near Zonnebeke), and finally to the Passchendaele Salient.

November 22, 1917 Sgr Ogilvie was struck-off-strength from the 4th CDA on being posted to the 4th Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery (CFA). On the same day he was taken-on-strength with the 4th Brigade, CFA. He actually ended up as a Signaller with the 21st Howitzer Battery, one of the Batteries in the 4th Brigade, CFA.

During his time with the 21st Howitzer Battery – 4th Brigade, CFA Sgr Ogilvie performed duties as a Signaller (Aldis Lamp, and Telephone Operator), Linesman, and Driver of horses carrying ammunition.

This is an excerpt from William George Ogilvie’s book where he describes his experience as a Lineman: ”Due to the heavy casualties of the past two weeks there were no linesmen available for duty at the Battery and the four of us Signallers were posted at this position had to take care their duties as well. A broken line had to be mended as soon as possible and whoever was off duty had to go out. At night this could be a risky task. Once outside of the telephone enclosure the linesman would pick up the telephone wire and follow it along until the break in the wire was located. When he found the broken end of the wire, he would mark the spot where he put it down and circle around to find the other broken end. Sometimes the gap between the two ends would only be a few feet, other times they might be a considerably further apart and would require a lot of searching to find them. When the two ends of the wire were located the linesman would remove the coil of wire from his shoulder and bare both ends with his pliers. He tied a reef knot, covering it carefully with electricians tape. When the break was mended he would take the lead from the field telephone he carried and with the safety pin which was attached to the end of the lead wire, jab the point through the insulating wire and try to put a signal through to the Unit which he hadn’t been able to reach before he set out. If he was lucky he would make the connection and could return to his bunk-hole and perhaps snatch a few hours of shuteye until it was his turn to go on duty once more. If he was unlucky he would have to continue on through the mud, the shellfire and the rain until he found and mended the next break. Three or four breaks in the line were not unusual when there was heavy shelling. Groping through or around shell holes, letting the foul, slime covered wire slip through your hand, trying not to lose your footing in the dark was a nightmare and you swore this was not a job fit for humans. Fortunately this task didn’t fall to us too often”.

There are no entries in Sgr Ogilvie’s Military File from November 22, 1917 and August 22, 1918.

The 4th Brigade Canadian Field Artillery War Diary indicates the following for this period:

On November 22, 1917 when Signaller Ogilvie joined the Unit, it was covering the Line from the northern edge of Fresnoy to the northern edge of Acheville. Everything was reported as being quiet with the weather fine, but cold, with a few flurries. On the 28th the Brigade was relieved and moved to a Rest area. ”This was a wonderful rest after the strenuous time at Ypres. Men and horses being well cared for”. On November 30th the Brigade moved out of its Waggon Lines to billets at Marles Les Mines.

Waggon Lines was an area well back of the Forward Batteries positions, beyond the reach of the enemy Artillery, where all equipment and materials associated with supporting the Batteries was located. This included: horses and wagons, as well as ammunition and other ancillary equipment. It was also a place where the men could withdraw to for a rest, meals and get cleaned up. Each night the guns and men of the Batteries would be resupplied with ammunition, rations, etc. from the Waggon Lines, under the cover of darkness.

December 1917 – the Brigade is getting squared away in its billets, which are described as very comfortable. Training has commenced with physical conditioning and exercise rides. Everyone, on a rotational basis, are taking baths and being issued clean underclothes. The weather is now described as very cold. The Brigade moved forward to positions in the area of Lens – Avion. December 25th was pretty much business as usual with the CO and Battery Commander scouting the countryside for suitable positions as the 21st Howitzer Battery was to move.

In his book, William George Ogilvie states: ”I don’t recall whether any Christmas turkey had been sent forward to us, though I rather doubt it. The Christmas mail, or some of it, did come through. These were exciting moments as the Christmas parcels were usually filled with all kinds of goodies: fruitcake, sweet biscuits, jams, socks, and knitted scarves. Needless to say we gorged on the goodies, especially the fruitcake. We were starved for sweets and made the most of it, neglecting our plain army grub”.

January and February of 1918 – were described as relatively quiet and very cold.

March 1918 – started quiet, until the 6th, when the enemy attempted a raid and entered Brigade trenches, but were driven out with heavy losses. A forward observation post, of the 4th Brigade, was destroyed with 1 NCO and 4 men wounded. The Brigade was taking calibration shots. On the 16th, another attempted enemy raid took place, but was once again driven back with heavy losses. On the 29th, the Brigade was relieved and moved to Acq. Acq was crowded with troops and billets were limited. The Brigade moved into action near Roclincourt, so Waggon Lines were again moved.

April 1918 – is once again quiet until the 25th and 26th, when the Brigade co-operated with the 11th Cdn Infantry Brigade in raiding enemy lines. The raiding party was successful, killings a number of Germans and capturing 1 Machine Gun. The night of the 27th and 28th, the Brigade put down a demonstration shoot with the objective of inflicting casualties on the enemy. If the weather and wind are favourable Gas Shells are to be used. April 30th the Brigade received orders to move.

May 1918 – on the 4th the Brigade (4th Brigade CFA) moved to Acq which was still overcrowded with troops. It started training in ”open warfare tactics”. On the 6th the Brigade moved to billets at Aubigny, which were less crowded, but heavy rain made the ground bad for training. On the 9th the Brigade was ordered to hold itself in readiness to go into action in short notice as an enemy attack was anticipated on its old front. The attack didn’t take place and the Brigade went back to practicing ”open warfare tactics”. It was reported that the Brigade was becoming very proficient in ”moving warfare tactics”. On the 22nd, the Brigade moved to the Magincourt area, with Batteries remaining in their Waggon Lines carrying out light training.

June 1918 – was a busy month, although the Brigade was still in the rear training. Training continued in ”open warfare tactics” but now included joint field maneuvers involving Tanks, Infantry and Artillery, as well as Bridging Practice, Map Reading, Lewis Machine Gun and Signaling Classes resumed. Later in the month, the Brigade marched to Amettes for calibration of Guns and firing practice on moving Tanks. The exercise was considered very successful. There were Church Parades, Inspections and even a Horse Show.

July 1918 – begins with a Corps Sports Day to celebrate July 1st (Dominion Day). It was considered a great success and was most appreciated by all participants. Training continued with practice on Lewis Machine Guns and rifle practice, map reading, and signals. They also trained in ammunition supply and coordinating advances with aero planes. There were also Inspections by Senior Commanders. On the 11th the Brigade marched to Mount St. Eloi, where they took up forward positions. On the 14th, the Brigade was back in action firing 500 18 pound and 150 4.5” rounds per day, around the clock, for several days on enemy positions along the Willerval Front. They also fired gas shells against enemy positions in the Arleux area. On the 28th the Brigade carried out a concentrated shoot of all forward guns on enemy positions. On the 31st the Brigade was relieved.

August 1918 – begins with the 4th Brigade at the Waggon Line at Mont St. Eloi. It now began a series of daily marches through Ampier and Vagnicourt, finally arriving at Bois de Boves on the 4th, where Waggon Lines were established. It is reported that a large number of troops were concentrated in the woods. August 5th, the Brigade moved into the Line and the Batteries took up positions. The enemy seemed suspicious as it increased its harassing fire, shelling the roads quite heavily at night. The Batteries of the 4th Brigade spent the 6th and 7th, getting ready for the Attack, with stockpiling ammunition. At 4:20 AM, on August 8, 1918 the Battle of Ameins began with a massive Artillery barrage up and down the Line, closely followed by an advance by the Infantry. This was the start of the 100 Day Offensive and the attack caught the enemy completely by surprise. As the Infantry advanced and consolidated its gains, the 4th Brigade Batteries moved forward as well, keeping pressure on the retreating Germans. On the 24th the Brigade was relieved and marched to its Waggon Lines at Ignacourt, followed by a series of moves through Toutencourt, Saulty, St. Quentin and Agny, finally setting up Waggon Lines east of Wancourt.

August 22, 1918 Sgr Ogilvie was granted a Leave from the August 22nd to September 5th. He rejoined his Unit on September 7, 1918.

While Signaller Ogilvie was on Leave, the 4th Brigade went into action southwest of Vis en Artois. Unfortunately, getting ammunition for the guns was a challenge as some of the ammo dumps had none. On September 3rd, with the enemy vacating the area to Canal du Nord, the Brigade moved forward to Rumancourt. On the 6th, the Brigade was relieved and took up a position at Etrun. From the 6th to the 9th the men and horses of the 4th Brigade rested after a strenuous few days. On the 9th both Pay and Church Parades were held, the Unit was inspected. The 4th Brigade next marched to Habarcq where time was spent exercising the horses, cleaning harnesses and equipment. On the 22nd it marched from Habarcq at 2 PM, halted at Agny, before proceeding to Croiselles. Here they spent their time hauling ammunition to its Battle positions southwest of Inchy. On the 25th the Brigade moved to its Waggon Line in the area of Quent and went into action. The 26th, was uneventful as it appeared that the enemy was not suspicious for there was little harassing fire. Everything was ready for the coming attack. On September 27, 1918 at 5:20 AM, began the Battle of Canal du Nord. A massive Allied Artillery barrage commenced with the Infantry going over the top. The 4th Brigade was prepared to move forward behind the advancing Infantry. The Brigade occupied positions just west of Canal du Nord and it opened fire at 8:20 AM. The Batteries of the 4th Brigade moved forward during the afternoon to an area north of Quarry Wood. It is reported that casualties were re-markedly light considering the rapidity of the move forward. At 7:30 PM the Brigade fired what was known as the Odlum Barrage. On the 28th, at 6:00 and 9:00 AM, all Batteries fired barrages, and proceeded to push forward to the valley south of Hayencourt. On the 29th, the Infantry attacked at 8:00 AM but met strong resistance from enemy Machine Gun positions firing from a railway embankment. One Section from each Battery moved forward in support of the Infantry. On the 30th the Infantry attacked once again and with Artillery support captured the railway embankment.

October 1918 – the Canadian Corps attacked enemy positions at 5:00 AM, progress was made, but owing to the strength of the enemy, who had been concentrating troops for a counterattack, the Infantry could not hold the gains. In support of the Infantry, the 4th Brigade fired 8,000 rounds of 18 Pounders and 1,800 rounds of 4.5” ammunition. On the 3rd the 4th Brigade made arrangement for a concentrated gas shoot using captured enemy guns and ammo. On the 4th the Brigade withdrew to its Waggon Line. On the 6th it marched, at night, to the neighbourhood of Vis en Artois. The 10th the 4th Brigade moved to an area near Dury and Recourt, in support of the 1st Cdn Div. With the enemy retreating, the Infantry and Artillery followed. From the 12th to the 15th the Brigade was busy firing barrages on enemy positions. On the 18th it moved to Roucourt following the retreating enemy. On the 20th it was relieved and marched to the area of the 4th Cdn Division marching to Bellevue. On the 23rd the 4th Brigade was in billets at what was described ”beautiful Beuvrages”. On the 29th, after withdrawing to its Waggon Lines, it moved into position near Tritch – west of the Canal.

November 1918 – at 5:15 AM, on the 1st the 4th Cdn Division attacked following the Line of the Canal towards Valenciennnes. The attack was entirely successful. All objectives being reached and many prisoners captured. The Batteries of the 4th Brigade CFA opened fire at 5:15 AM, in support of the Infantry advance and stopped firing at 8:50 AM. On the 2nd, the Brigade moved forward to the outskirts of Valenciennes, in anticipation of an enemy counterattack which didn’t occur. On the 4th the Brigade moved to Estreux, in close support of advancing Infantry. On the 5th, at night, it advanced to the neighbourhood of Rombies. At dawn it fired a barrage on enemy positions which was repeated at dawn on the 6th. On the 7th, the Brigade was in billets in the vicinity of Valenciennes, where it stayed until the 16th. On the 10th, the President of the Republic of France visited Valenciennes and gave a speech at Place D’Armes. On November 11th at 11:00 AM hostilities ceased. There was no apparent excitement in the 4th Brigade. From the 12th to the 16th preparations were underway for the Canadian Corps to march to Germany. On the 16th the 4th Brigade marched from Valenciennes to Elougnes, where it would remain until the 20th. On the 20th it left Elougnes at 7:15 AM and marched in Column to Cuesmes, which was a mining town on the outskirts of Mons. It was reported the billets were fair but provided no cover for the horses. The mines were well equipped with bathes and the men were able to cleanup. The rest of the month was spent with the men resting and caring for the horses. On the 27th, the King of Belgium visited Mons and gave a speech.

December 1918 – December 1st all Batteries working hard for Inspection tomorrow. On the 2nd the 4th Brigade was inspected by the General Officer Commanding of the 4th Canadian Division. On the 3rd the day was spent playing football. Also, reading and writing classes started. From the 3rd to the 11th was spent resting, and taking care of horses. On December 11, 1918 Sgr Ogilvie was treated at the No 13 Canadian Field Ambulance (CFA) with Influenza. On the same day he was processed at No 5 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station (CCCS). On December 17 he was at No 55 CCCS and on the 18th he rejoined his Unit. While Sgr Ogilvie was being treated for Influenza, on the 12th, the 4th Brigade marched from Cuesnes, through Mons, to Haine St. Paul, Belgium, where the billets were described as very good for the men. The weather was reported as very poor (heavy rain). Now began a series of almost daily marches finally ending up at a Chateau, near Aische en Refail, Belgium where the Brigade would spend the rest of the month. Christmas Day dawned with a thin coating of snow on the ground and the 19th, 27th, and 21st Batteries had their Christmas Celebrations.

January 1919 – the 4th Artillery Brigade received Orders that it would soon be moving to an area closer to Brussels, Belgium. All Batteries began preparations for the move. Now began a series of moves taking the Brigade to Ottignies, Belgium on the 4th. The 4th Brigade would stay at Ottignies through to the end of March. The time was spent in parades, attending educational lectures, exercise rides, public dances and football games.

The 4th Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery War Dairy ends March 1919.

On March 19, 1919 Sgr Ogilvie was granted a Leave from March 19, 1919 to April 2, 1919. He rejoined the 4th Brigade, CFA on April 8, 1919.

On April 25, 1919 Signaller William George Ogilvie proceeded to England.

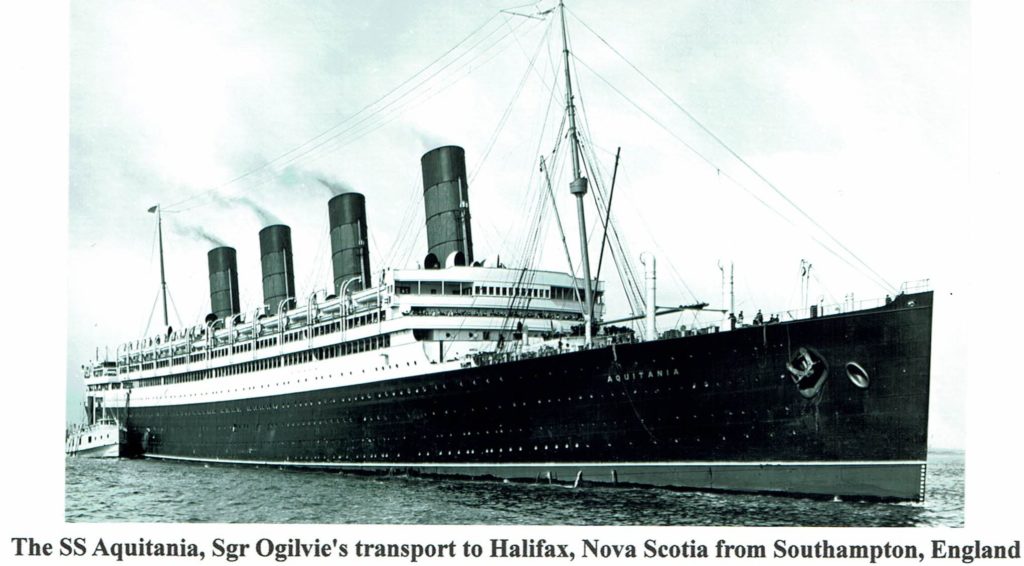

On May 19, 1919 Signaller William George Ogilvie was struck-off-on-strength from the 4th Brigade, CFA on return to Canada. Signaller William George Ogilvie’s Military File indicates, he embarked about May 18, 1919 from Southampton, England aboard the SS Aquitania, arriving in Halifax on May 25, 1919.

In Halifax Sgr Ogilvie boarded a train which took him to Toronto where, on May 25, 1919, he was taken-on-strength with No 2 District Depot, Toronto Ontario, located in the Exhibition Grounds.

Signaller William George Ogilvie was discharged from His Majesty’s Service at No 2 District Depot on May 27, 1919. His physical condition upon discharge was considered good.

Based on his Military File, Signaller Ogilvie served a total of 2 years, 9 months and 4 days with the Canadian Expeditionary Force: 3 months and 2 days in Canada, 8 months and 4 days in the UK, and 1 year, 9 months, and 12 days in France.

There is no mention in the File with regards to what Military Medals Signaller William Georeg Ogilvie was eligible to receive or was awarded. Based on his Military Service, he was awarded the:

British War Medal; and

Victory Medal.

He would have also received the CEF Class “A” War service Badge.

An excerpt from an article in Maclean’s by Barbara Ameil, September 1996:

The Military is the single calling in the world with job specifications that include a commitment to die for your nation. What could be more honorable.

PERSONAL HISTORY

WILLIAM GEORGE OGILVIE

William George Ogilvie was born March 7, 1899 in Lakefield, Ontario; son of George Gilbert Ogilvie and Elizabeth Shannon. William George went by the nickname “Bill”. He was educated in Lakefield’s Public and High School in Lakefield where he was a member of the Army Cadet Corps.

Bill was a typical Lakefield boy of his time; spending his leisurely hours swimming from the docks of the boathouses built on what is now the northern part of Isobel Morris Park. The water often had large booms of logs waiting to be milled, and he and his friends spent many fun filled hours skipping across the timbers. Bill hunted often as the area south and east of his home was then open land, clear to Buckley’s Lake. He owned a canoe and through that means paddled and camped extensively in season on Katchewanooka, Clear and Stony Lakes.

Bill spent many pleasant hours riding the family horse. Church was a big part of Bill’s life, he was a member of St. John’s Anglican Church where he attended the Young Peoples group.

Patriotism, with the urging and support to serve, was rampant in the community – and it was catching! At the end of the years’ classes in the summer of 1916 and having attained the age of 17 years, Bill went in to the Peterborough Armories and joined the Army on August 23, 1916.

Such was the fervour and support of the Lakefield community that each boy, or group, was sent off from the local train station with a large crowd, including a few spokespersons, a band and, most often, the gift of an engraved watch. Bill dreaded all this pomp and splendour on his behalf so he got a ride to Peterborough and caught his train from there, skipping the local farewell. Our local well-wishers eventually eased their disappointment and mailed the watch to Bill at his camp in Petawawa!

In May 1919 Bill happily returned to Lakefield and wasted little time in getting his canoe back in the water! A lovely summer lay before him.

William George Ogilvie married Ruth Grace Blaisdell in Toronto, York County on March 15, 1924. Bill and Ruth Grace had a son; Hugh Gilbert, born November 8, 1924, died October 6, 1961 and two daughters; Sunny and Wendy. Bill and his family lived in Toronto. Circa 1951 Bill divorced Ruth Grace and subsequently married Grace Archer. Bill sold large yachts and spent his summers in the Muskokas.

In later years, about 1975, Bill moved back to the family home on Ermatinger Street. In 1982, Bill wrote this fine book describing, in an entertaining manner, his WW I experiences. It is titled “Umty-Iddy-Umty”. Our Smith-Ennismore-Lakefield library has same for your enjoyment. Bill lived a quiet life at Green Gables pursuing his interest in writing, painting and reading until his passing in June of 1992. William George Ogilvie is buried in the family plot in Lakefield Hillside Cemetery.

THE WILLIAM GEORGE OGILVIE FAMILY OF LAKEFIELD

William George’s paternal grandparents are William Cecil and Louisa Letitia Ogilvie. William Cecil and Louisa married in England. They had at least seven children: Eliza L.; Charles; Frederick H.; Caroline F.; George G.; Maria L.; and Henrietta.

William George’s parents George Gilbert Ogilvie, born February 7, 1851 and Elizabeth Shannon, born November 26, 1855 in England were married in Douro Township on October 20, 1891. George Gilbert and Elizabeth had four children: Henrietta (Etta), born in Lakefield, Ontario January 12, 1893, remained at home and kept house for her father after her mother died, Etta died September 5, 1986; Mary Letitia, born in Lakefield May 12, 1894, died February 4, 1946; Elsie Caroline, born in Lakefield August 10, 1895, died August 18, 1965 and William George, born in Lakefield March 7, 1899, died June 3, 1992. George Gilbert Ogilvie immigrated to Canada in 1868, he was a surveyor on the International Boundary in 1873-74. George Gilbert Ogilvie died March 15, 1945. Elizabeth Ogilvie died June 14, 1910.

In 1901 the Ogilvie family lived in Douro Township, Peterborough County, Ontario. The family home was on the south side, on what was then the east edge of Ermatinger Street, where they had 18 acres of property known as “Green Gables”. Initially the home was located in Douro Township; later the Village of Lakefield incorporated the family home and property into the Village of Lakefield and extended Ermatinger Street.

As did many families, they too owned a horse and Church was a big part of family life. They were members of St. John’s Anglican Church. On Sundays, there were three services; the morning service, afternoon Sunday school, and the evening service. By 1911 Elizabeth had died. Then in 1921 only George Gilbert and his daughter Henrietta (Etta) were still in the family home. At some point after 1921 Elsie Caroline and Mary Letitia, who had moved to Toronto and became a trained nurses, returned to the family home. Mary Letitia died February 4, 1946 from cancer in Toronto and is interred in the family plot in Hillside Cemetery, Lakefield.

OLD SOLDIERS NEVER DIE

“Old soldiers never die; they simply fade away.” Perhaps there is more truth than poetry in that old saying for I must confess that I am an old soldier now and I am slowly fading away – shrinking away might describe the process better.

I can’t delay the encroachment of old age and before it goes too far I have decided to attempt to recapture my soldiering days in the First World War, from the time I enlisted at the age of 17 in the spring of 1916, until I was honourably discharged in May 1919.

The late William G. Ogilvie fondly known as “Bill” to Lakefield residents wrote his memories as a World War I soldier in a book entitled, Umty-Iddy-Umty – The Story of a Canadian Signaller in the First World War which was published in 1982.

Bill was born in 1899 and passed away in 1992, 10 years after Umty-Iddy-Umty was published. The book is dedicated to his fellow comrades who did not make it back to the land of their birth. In his memoirs, Bill describes Lakefield in the early 1900s as, “an interesting little village of about fifteen hundred residents … the beautiful Otonabee River wound its way through the village.”

He describes his life as “happy and uneventful”. Days were spent hunting with friends, riding his horse and paddling or sailing up Katchewanooka Lake to Clear and Stoney Lakes. Bill’s mother died when he was about nine years old. He had three sisters, two of whom moved to Toronto to train as nurses. This left Bill, his oldest sister, Henrietta, and his father, George Gilbert Ogilvie living in their charming home known as “Green Gables” on Ermatinger Street in Lakefield.

Bill was 15 years old when war was declared on August 14, 1914. The war did not have much meaning for him at that young age. “I attended Lakefield High School in 1916 and by then all the talk of war made learning … seem a waste of time…”

By this time, Bill, like many others his age, was caught up in the feeling of patriotism and he enlisted to “escape schoolwork” and because “King and Country” needed him.

As a new member of the 74th Recruiting Battery, Bill describes his amazement at the use of colourful language and four letter words since such language was seldom heard in our quiet little village.” He soon realized he didn’t fall far behind the others with his own verbal abilities while trying to drive a mule to water one day. “It seemed to be the only language that the obstinate animals understood.”

At Barrifield Camp near Kingston, Bill initially trained to be a driver rather than a gunner since he was comfortable with horses and riding. Before long, though, training offered for artillery signalers began to appeal to him. They (signalers) had very little fatigue work, just classes where they learned flag wagging and dot-dash of the Morse code, or umpty-iddy-umpty as it was generally called.,”

When Bill’s draft was called, he travelled to Halifax by train and soon found himself on his first voyage. He quickly found his “sea legs” on the rough passage when many were not so fortunate. Everyone aboard was glad to finally dock at Southampton, England. After arrival at Riseborough Barracks where the 4th Canadian Reserve Artillery was located, signal classes, riding school and outdoor exercises filled his days. Bill’s first taste of war came at the barracks one day when bombs began to fall in a straight line through the married couples quarters and on towards a nearby town.

Bill enjoyed three or four pleasant six day leaves at his Aunt Carrie Leigh’s house in Choleywood, a suburb on the northern side of London. Prior to his enlistment, Bill had never met his aunt who was a widow and lived with her daughter Maud in a large four bedroom brick home surrounded by a large garden. Bill felt very welcome and found time spent there to be pleasant.

Upon his returning to Riseborough Barracks from his final leave, he found that the signaling classes were more intense, marking the approach of the inevitable call to the battlefront. From time to time at Riseborough, the men had the opportunity to visit Folkestone, Dover or Hyke. On one such trip to Hyke, Bill was thrilled to “find a boat rental place which stocked the famous Lakefield cedar-strip canoes.”

The Lakefield Canoe Company had won a string of gold medals for its canoes at various European Expositions and here in Hyke were 20 or more of these Lakefield canoes for hire. “I lost no time in securing one and enjoying my first paddle abroad in my hometown product.” Marching orders were received and were immediately followed by the crossing of the English Channel, and a long hot march to Etaples, France. A ride in dark, cramped box cars lined with lice infested straw pre-empted their arrival behind the Lens front where Bill found himself under the command of Major Richard Phippen from Toronto.

When Major Phippen learned that Bill was from Lakefield, he asked Bill if he knew Geoffrey Hilliard with whom he had attended Royal Military College in Kingston. When Bill explained that the Hilliard’s were neighbours of his in Lakefield, the Major became quite friendly and did what he could to ease Bill’s initiation to the battlefront. Bill did not find his duties as a signaler taxing. Among other duties, such as tending to the horses, Bill spent four hours on telephone duty and four hours off.

On August 15, 1917, Bill learned that the Battle of Hill 70 had been fought that morning. He and another signaler were called to Major Phippen’s office and were ordered to follow the advancing troops toward Hill 70 in search of German telephone equipment. The two rookie signalers came upon the ongoing battle and immediately went to work carrying many injured soldiers to safety. Bill and his comrade eventually returned wearily to the safety of their camp having visited their first battlefront. Hill 70 had fallen.

In October of 1917, the 4th Brigade made camp at Vlamertinghe and Bill describes his days in France as grueling while they coped with incessant rains, dangerous passages amidst shelling, roads covered in debris and dead horses and many wounded comrades. Bill suffered a bout of trench fever which took some time to recover from.

Bill described, in detail, the sight of German observation balloons being shot down by a lone Royal Flying Corps pilot. The occupants of the balloons parachuted to safety. A German fighter plane shot the plane down with tracer bullets and Bill recalled his feelings of contempt as he watched the German fighter plane double back to shoot the pilot who had parachuted out of the fallen plane.

At Passchendaele Ridge, Bill was required to buzz all units every half hour and report to headquarters if any could not be reached. In addition, he and his comrades were assigned to linesman work which entailed following the telephone lines and fixing breaks, difficult and dangerous work often done in the dark of night. After 14 months spent in France, Bill enjoyed another brief leave at his Aunt Carrie’s home in England. He recalls that on this particular leave, he had to watch others at dinner to determine when to use a spoon or fork; formalities he had long since forgotten.

On his return to the battlefront, Bill directed the shelling of a live target just below Vimy Ridge when he spotted the flash of a German battery firing. Their troops made steady advances against the enemy day by day. Bill recalled the barrage of gunfire and extreme hunger and fatigue. It was when his brigade was sent for a rest to Valenciennes that good news finally arrived. “The shouting, far up the street, was getting louder and we were finally told that an armistice had been signed and that the war was over. We just couldn’t believe it … it was quite some time before good news filtered into our benumbed minds, that the war was all over and that we had survived.”

Bill contracted influenza and was hospitalized in France in mid-November 1918. Near the end of April, he boarded a ship from England to Canada. Bill was met at Union Station in Toronto by his two sisters, Elsie and Mary where a brief but joyful overnight reunion took place before he boarded a train to return to Lakefield.

“Our home stood on 18 acres on the edge of the village. There was a long row of poplars bordering the winding drive and at the rear of the drive lay an apple orchard. Three years was a long time to be away. The house was smaller than I remembered and the lawn even seemed to have shrunk. Even my father and sister, Henrietta, who were there to greet me, looked smaller than before. I lost o time in getting my canoe down from the drive shed … a whole lovely summer lay before me.”

Through the years, William George Ogilvie worked as a yacht broker, salesman, wartime government inspector and operated a boat business for over 60 years. A columnist for the Muskoka Sun, Bill was also an essayist and short story author, writing several books including Silver Toes, a children’s series.

Bill’s father, George Gilbert Ogilvie (1851-1945), surveyed the international boundary in 1873-74 and travelled as far as Texas before returning to Lakefield.

Through the years, Bill’s three children, Hugh, “Sunny” and Wendy enjoyed time spent away from Toronto at Green Gables in Lakefield. Bill spent much of his career living in Toronto and returned to Green Gables in Lakefield where he lived with his sister, Henrietta, until she was admitted to the Lakefield Private Hospital.

Every single day for years, Bill, the old soldier, could be seen walking from the east end of the village to the Lakefield Private Hospital to visit her. The Ogilvie family of Green Gables is remembered with fondness and respect by friends and neighbours in the Village of Lakefield.

(Article by Patricia Heffernan typed from The Lakefield Herald dated Friday, November 9, 2012)